We have all done and experienced things we would rather forget about if we could, and then there are those things we should really remember but just can't seem to recall — from the benign, like that new neighbor's name, to the potentially life-altering, like what happened that night we got really drunk.

Selective memory affects all age groups, from teens to young adults and middle-aged people to senior citizens, though not always for the same reasons. Neurological condition and substance abuse aren't the same thing, after all.

A few different theories exist, of course. Freud came up with the term childhood amnesia in 1910, and said it "veils our earliest youth from us and makes us strangers to it". Why? We're talking about Freud, so the answer is unsurprisingly "sexual trauma". Until a few decades ago, the more popular theory was that young kids simply don't create memories, either because nothing really exciting happens at that age or because the brain is too immature to do so.

When Do The Earliest Memories Appear?

"When do the earliest memories appear?" might appear to be a sane thing to ask, but it looks like scientists were asking the wrong question. Any parent who currently has young children probably knows that even very young kids (aged roughly between two and five) are definitely able to recall things that happened in the past. Sometimes those things took place only weeks ago, but many kids are definitely able to go back much further.

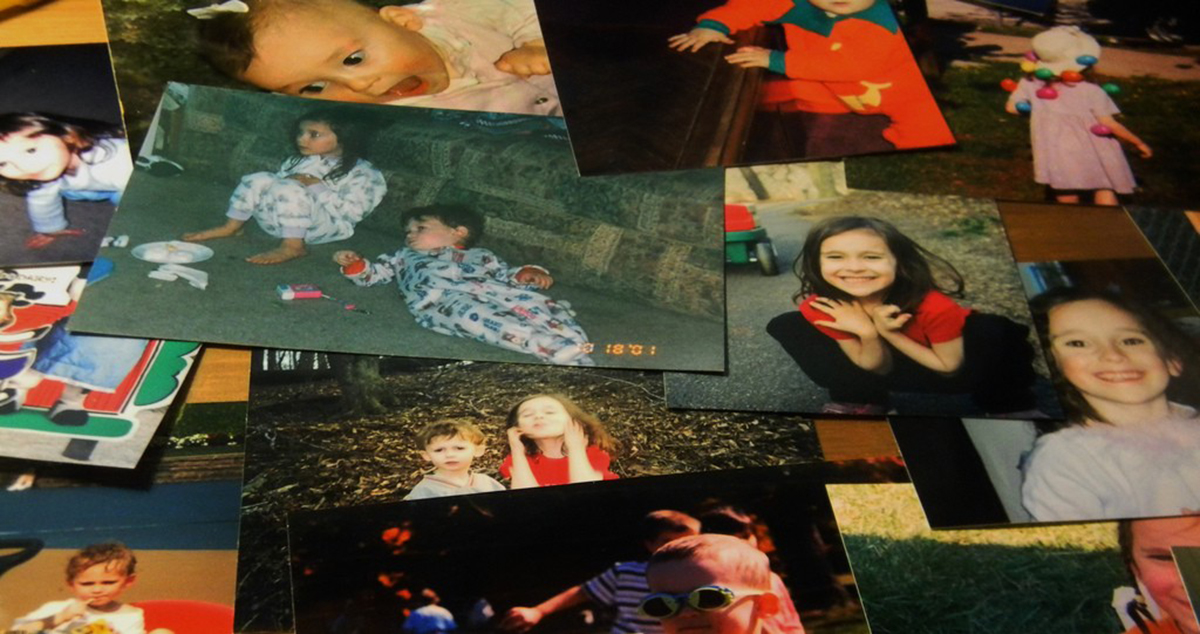

I asked my children, five and eight years old, to talk about some things they remember from "long ago". My son talked about a neighbor at our old house giving him chocolate, and we moved more than two years ago. He also recalled jumping on a bouncy castle in our old neighborhood. My daughter remembered having a bad fall when she was five, but doesn't remember her brother being born when she was two, though she was at the birth. Neither can she recall her great grandmother dying when she was three.

This small selection of things remembered and forgotten is bound to sound familiar to many parents. It is also in line with research recently conducted by Carole Peterson from Memorial University of Newfoundland. Peterson and her colleagues wanted to find out what happens to those early childhood memories, where they go and when we lose them.

'Earliest Memories' Replaced Over Time

The team interviewed 140 kids aged between four and 13, asking them to describe their three earliest memories. Parents stood by to confirm that the memories the children relayed were of things that really did happen. All kids, even the four-year olds, were able to describe early memories.

The youngest children could describe events that happened when they were about two years old. Two years later, the research team followed up to see if the subjects had any amnesia. They found that more than a third of the over-10s retained the memories they had initially described, while the very youngest kids had mainly forgotten.

See Also: How to Improve Memory: 10 Simple Tips

As children get older, their "earliest memories" change. Memories that were vivid at first get replaced with newer memories, up until about age 10 when their memories "crystallize", Peterson explains.

What Memories Are Most Likely To Stay Strong?

What memories are most likely to stay strong over time? Peterson and her team did conclude that children were three times more likely have memories of very emotional events two years later, but she also notes that only a very small portion of the earliest memories her study subjects reported were of very stressful or traumatic events.

Peterson and her colleagues have now moved on to studying why some memories are retained, while others are forgotten. The outcome of that research will, undoubtedly, offer new and fascinating insights into the inner workings of the human brain.

When the research team looked at the memories of both Canadian and Chinese children, they discovered that Canadian kids' earliest memories tend to have occurred a year or more before Chinese kids' earliest memories. Robyn Fivush PhD from Emory University, another child memory researcher, compared the memories of American and Chinese children and reached the same conclusion. Fascinating, but why?

Western children and their parents, Fivush said, are more likely to have "autobiographical dialogues". In other words, American and Canadian children might be able to recall events that took place earlier, because they talk about themselves a lot during the early years. This can be explained by the fact that individuals are emphasized more than the collective in Western cultures, while Asian cultures tend to do the opposite.

What's In A Memory?

Memories are made up of many different parts. They might include recollection of conversations, feelings, visual information, non-word auditory information, smells, and tactile experiences. These "loose bits of info" need to be bundled together for the brain to recognize them as being part of a single memory. That sounds like a complex process, and it is — several parts of the brain are required.

The cerebral cortex processes these raw bits of info, but the hippocampus links the separate experiences together. Since the hippocampus isn't fully developed until later in adolescence, it is quite likely that it forms part of the reason kids can't seem to hold onto their very earliest childhood memories.

See Also: Two Great Habits That Sharpen Your Focus And Improve Memory

On the other hand, it is also possible that memories are lost because the relevant synapses wither away when they are not used, or because the brain needs the synapses for something else.

Finally, young children — most of whom are not able to use clocks and calendars — often simply don't have a good sense of the point in time during which something happened. This explains why some kids say things that happened weeks ago happened last year, or vice versa. It is also why you might remember that childhood holiday, but can't recall how old you were at the time

- Photo courtesy of David Mican by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/davidmican/315728765

- Photo courtesy of martinak15 by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/martinaphotography/6352138730