Something strange is happening in the recent decades: new deadly viral infections, never seen before, are emerging and threatened millions of people. HIV, SARS, MERS and avian flu are the examples of such infections that got significant publicity and attention. What unites all these infections together is the fact that all of them originate from the wildlife. Viruses previously unknown to affect people are suddenly found in human populations and even, like HIV, spread worldwide.

MERS (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome) is an interesting recent example. The virus causing this illness was first identified only in September 2012. By August 2013, around 100 patients, mostly in Saudi Arabia, were diagnosed with MERS, and half of them died as a result of this infection. The virus was declared by WHO as a “threat to entire world”. The source of the virus was traced to Egyptian tomb bat: most affected patients lived in or close to the buildings where these bats were found.

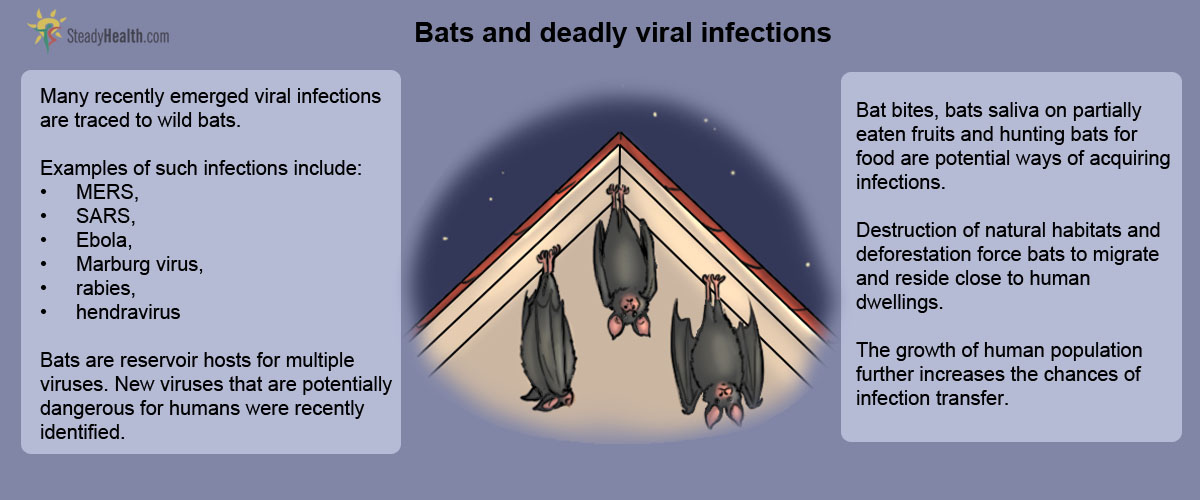

Bats are often associated with newly emerging viral infections

MERS is not an isolated example when viral infection gets transferred from bats to humans. Research has identified several horseshoe bat species from the genus Rhinolophus as the reservoir hosts for coronavirus that is associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The SARS outbreak in Southeast Asia in 2002 -2003 affected more than 8000 and killed 774 people. It was reported to be transmitted by Chinese Horseshoe bats. These bats are seen in China, India, Nepal, and Vietnam.

Ebola virus and Marburg virus, the infectious agents behind the viral hemorrhagic fever, got notoriety due to their deadly nature. These viruses belong to the Filoviridaefamily. Cases of Ebola virus infection have been reported in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Sudan, Ivory Coast and Uganda. Closely related Marburg virus was first found in 1960s in Europe in German cities of Marburg and Frankfurt, as well as Yugoslavian capital Belgrade. Unusual location of this outbreak provided ground for a number of conspiracy theories about genetically manipulated and artificially produced deadly viruses.

There is no specific treatment for viral hemorrhagic fever caused by either of these two viruses. Supportive therapy in the form of intravenous fluids, oxygen inhalation, blood transfusion and organ system support is usually given in the hope that natural immune system will struggle the infection off. The patients are also kept in isolation since disease is highly contagious.

There are several other, less common, viral infections that can also be transferred by bats and, on some rare occasions, infect humans. Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV) is related to rabies virus and may be transmitted by bite of a bat. It results in rabies like disease in human population and is usually fatal. The incubation period is 4 to 5 weeks. It is a very rare disease and few cases were reported in Australia. All infected persons have died. Rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin against rabies is protective against this virus.

Read More: West Nile Virus

Hendravirus, Nipah virus and Cedar Virus belong to the family of viruses called Paramyxoviridae. Hendra virus was first identified in 1994 in Australia after the death of one human and ten horses. These viruses are transmitted by Pteropid fruit bats or flying foxes. This infection is transmitted to human hosts by close contact with body fluids of infected horses. The horses get this infection from the fruit bats by eating food recently contaminated by flying fox urine or saliva and develop lung edema, congestion and neurological features. These viruses are not transmitted directly to humans.

Deforestation And Growth Of Human Population Might Be Behind The Increasing Number Of New Bats-Transferred Infections

The diseases transmitted from animals to humans are called zoonotic diseases. They emergence primarily depends on the human-animal interaction or the nature of this contact. The viral infections originating from bats belong to this class of diseases. But what is the connection between humans and this rather unusual disease carrier? And why no troubles were recorded in the past?

It looks like most viruses in question happily exist in the body of bats without causing them much trouble. Bats act as so-called reservoir hosts. Rapid growth of urban landscape has brought humans closer to bats, thereby increasing the risk of transmission of many diseases. Changing climate patterns and deforestation leads to the destruction of natural habitats and results in migration of bat populations closer to human settlements.

Rabies is one of the most common viral infections that can be transmitted by bats

Exotic viruses mentioned above are not the first bat-transferred infectious agents ever recorded. In fact, the first detection of viral disease transmitted by bats occurred in 1920s when rabies virus was detected in bats in Central and South America.

The saliva of a bat contains rabies virus and exposure of any wound or mucous membrane lining eyes, mouth and nose may result in viral penetration and rabies. It is therefore more common among cave explorers. In certain areas, human contact with bats has increased due to expanding population and bat migration. Bats also live on trees and partially eaten fruits stained with bat saliva are a source of infection.

Bats host a number of other viral infections that can potentially be dangerous for humans

A research article published several years ago in the journal Current topics in microbiology and immunology mentioned that many of the common viruses like measles, mumps, respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza viruses have been detected in bats.

Read More: Meet The Invisibility Cloak That Will Protect You From Mosquitoes

Recent study published by the researchers from the University of Cambridge revealed that the tropical bats populations can serve as a natural reservoir for even more different viral infections than previously thought. Scientists have analyzed 2,000 bats from 12 African countries and found that almost half of the animals harbored various viruses such as rabies-like Lagos bats virus and henipavirus.

Fruit bats tend to eat some fruits that are also consumed by people. The partially eaten fruits can contain the traces of virus-infested bats saliva which may cause the transfer of infection. In addition, many tropical species of bats are hunted for food by local people. Growth of human settlements increases the chances of occasional viral transfer that might become a starting point of infections outbreak.

- Wang LF, Shi Z, Zhang S, Field H, Daszak P, Eaton BT. Review of bats and SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Dec,12(12):1834-40

- Gibbons RV. Cryptogenic rabies, bats, and the question of aerosol transmission. Ann Emerg Med. 2002 May, 39(5):528-36

- Robert Swanepoel, Sheilagh B. Smit, Pierre E. Rollin. Studies of Reservoir Hosts for Marburg Virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 December, 13(12): 1847–1851

- Warrilow D. Australian bat lyssavirus: a recently discovered new rhabdovirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005, 292:25-44

- Wang LF, Eaton BT. Bats, civets and the emergence of SARS. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2007, 315:325-44

- Alison J. Peel, David R. Sargan, Kate S. Baker et al. (19 November 2013) Continent-wide panmixia of an African fruit bat facilitates transmission of potentially zoonotic viruses. Nature Communications 4, Article number: 2770

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of USFWS Headquarters by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/usfwshq/7256670496/

Your thoughts on this