Table of Contents

Arguably, HIV is a largest pandemic in human history. Since HIV was confirmed as the cause of AIDS in 1984, more than 35 million people have died and the virus continues to steadily spread worldwide. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the most affected area in the world, 1 in every 20 adults is infected.

Modern antiretroviral drugs transformed HIV treatment and management

In spite of the severity and propagation of this infection, to this day there is no cure for HIV. However, the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has improved quality of life and life expectancy for patients infected with HIV.

Combined, they target almost every step of the viral life cycle. This has revolutionized the lives of affected patients globally, making HIV infection a chronic, manageable disease, instead of the fatal infection it once was.

HIV pandemic continues to grow

Although the knowledge about the routes of HIV transmission is greater than ever, putting an end to the HIV pandemic seems hardly achievable, with more than 7,000 new cases of infection being registered every day. Furthermore, ART therapy can take a huge financial toll on both patients and healthcare systems. This is aggravated by the fact that HIV infection is more common in the developing countries where access to treatment is frequently impaired and economic sustainability is a full-time problem.

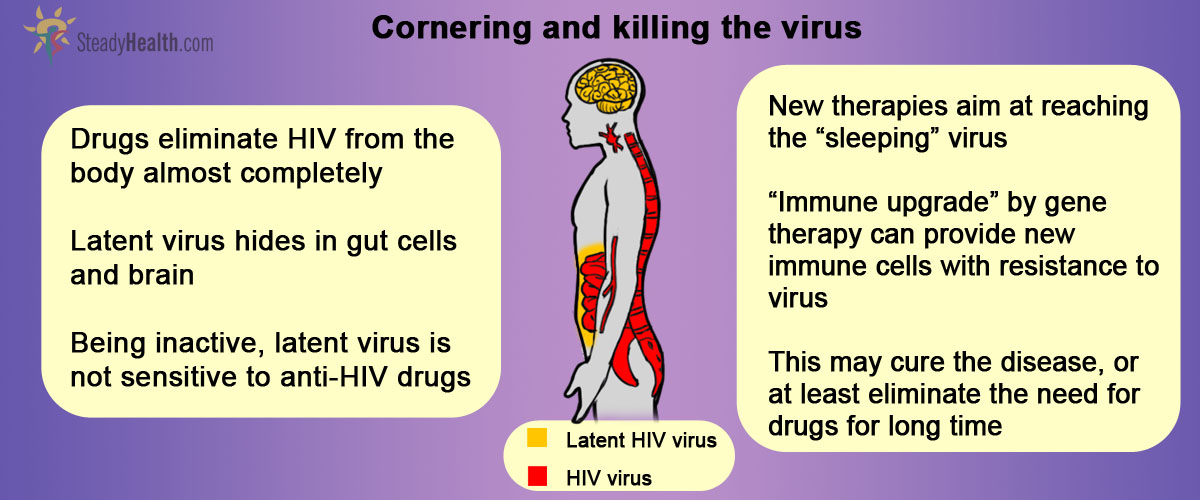

ART cannot fully eradicate virus

Why it is that ART therapy cannot eradicate the HIV infection completely, though? At the root of the answer for this question lies what is called HIV latency. HIV latency refers to the rare but extremely stable viral reservoir formed within the so-called resting memory CD4+ T cells.

CD4+ T cells are the cells of immune system where the HIV virus normally resides. Newly produced (“naïve”) CD4+ T cells get exposed to various antigens (harmful pathogens coming from our environment) and become activated. This activation triggers a chain of events that result in the elimination of pathogen. For the most part, the activated T cells die within weeks of the encounter with the antigen. A minority, though, reverts to a resting state and persist as memory T cells which give the immune system the capability of responding more immediately to the same antigen in the future. It is precisely within these cells that latent HIV viruses form reservoirs. Because these cells persist in the body for long periods of time, the latent virus can be maintained indefinitely, away from the action of regular antiretroviral drugs.

See Also: Breaking News! Potential HIV Cure Found - A Protein that Entombs HIV

This constitutes, then, a major obstacle to achieving cure.

- DOUEK, D. C. 2013. Immune Activation, HIV Persistence, and the Cure. Topics in Antiviral Medicine, 21, 128-132

- PASSAESA, C. P. & SÁEZ-CIRIÓN, A. 2014. HIV cure research: Advances and prospects. Virology

- KENT, S. J., REECE, J. C., PETRAVIC, J., MARTYUSHEV, A., KRAMSKI, M., ROSE, R. D., COOPER, D. A., KELLEHER, A. D., EMERY, S., CAMERON, P. U., LEWIN, S. R. & DAVENPORT, M. P. 2013. The search for an HIV cure: tackling latent infection. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13, 614-621

- LAFEUILLADE, A. & STEVENSON, M. 2011. The Search for a Cure for Persistent HIV Infection. AIDS Reviews, 13, 63-66

- RUELAS, D. S. & GREENE, W. C. 2013. An Integrated Overview of HIV-1 Latency Cell, 155, 519-529.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Lwp Kommunikáció by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/lwpkommunikacio/12971165295

Your thoughts on this