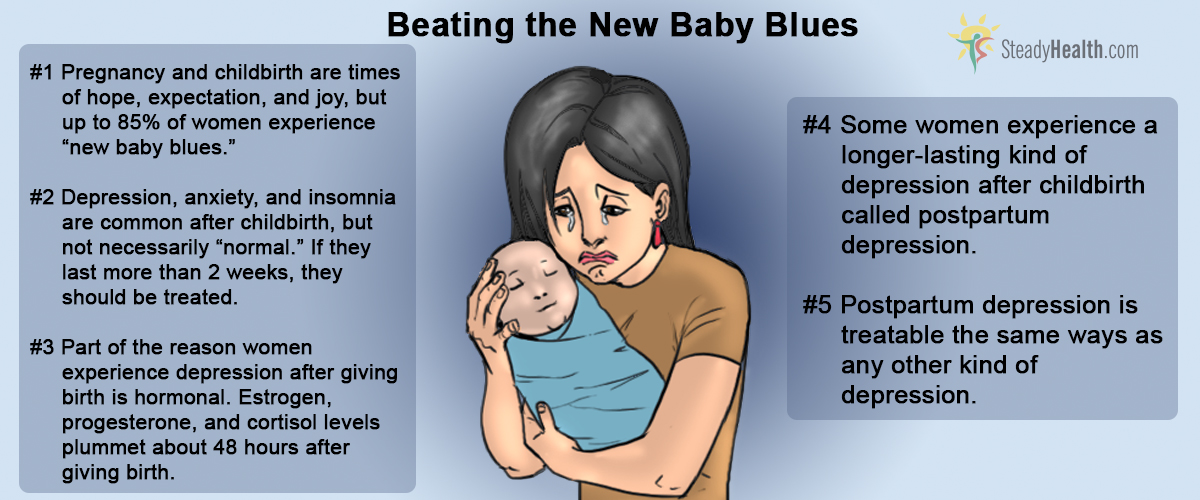

Postpartum depression, the appearance of feelings of sadness and fatigue after giving birth to a baby, are not at all unusual. In fact, as many as 85% of all women may experience some degree of a diagnosable mood disorder within the first year of giving birth.

Most of the time, these new baby blues don't last very long and don't cause debilitating depression. In up to 15% of new mothers, however, postpartum depression can be both disabling and persistent, and 1 or 2 mothers in 1000 experience postpartum psychosis, a severe derangement of psychological functioning triggered by giving birth.

Why Is Postpartum Depression So Common?

The reason why nearly all new mothers experience some degree of postpartum depression is biological. A new mother's estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol levels all fall drastically during the first 48 hours after giving birth. Their energizing effects come to an abrupt halt.

Amounts of these hormones, however, don't determine whether the postpartum mood changes are mild or severe. And giving depressed mothers of newborns estrogen replacement therapy actually can make depression worse.

The difficulty of the pregnancy, having to deal with complications of pregnancy, does not seem to have any direct bearing on the severity of postpartum depression, although finding out a child has been born with birth defects or health challenges, understandably, almost always does.

The most significant factors in the severity of postpartum depression are about more than just the experience of pregnancy and childbirth. Researchers have found that:

- Partner violence is more common in women who suffer postpartum depression, and healthcare providers need to be sensitive to the new mother's needs for physical protection when depression is diagnosed.

- Women who have experienced a recent death in the family, who have financial difficulties, or who cannot find needed employment are more likely to have to deal with postpartum depression. And, significantly,

- Women who have had to deal with postpartum depression after the birth of one child have a 90% chance of having to deal with another round of postpartum depression after the birth of another child.

Postpartum Depression Is Common, But Not "Natural"

Too often doctors dismiss depression in mothers of newborns as only natural. Most women suffer some degree of depression after giving birth, so it must be OK. But the fact is that many women continue to experience postpartum depression for months or even years after the birth of the child, affecting not just their quality of life but also the quality of life of the child and the entire family.

See Also: Baby Blues and Postpartum Depression (PPD): Causes and Treatment

When depression, tearfulness, irritability, and anxiety peak four or five days after the birth of the child and go away within 2 weeks, most doctors will not attempt any kind of intervention, but when feelings of fatigue, sadness, anger, anxiety, and/or depression persist for 2 weeks or more, medical intervention is a must.

When Is Medical Help Clearly Needed?

Certain kinds of symptoms are a sign that a mother's psychological discomfort is no longer new baby blues but instead a full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Inability to remember a distressing event in pregnancy.

- Inability to stop thinking about a distressing event in pregnancy.

- Flashbacks and/or nightmares.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Hypervigilance, being extremely aware of the baby's environment or her own.

- Problems with concentration.

- Attempting avoid reminders of the pregnancy.

The morphing of events in pregnancy or delivery into a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may occur insidiously over a period of 2 to 3 months. It is almost as if the PTSD "sneaks up" on the new mother. There may be such intense sadness or anxiety that the mother is unable to take care of her infant or herself.

Postpartum psychosis develops much more quickly, usually within 48 to 72 hours of the birth, usually in the first two weeks. Women who experience this condition may experience severe mood swings from paralyzing depression to elation, along with insomnia, irritability, and disorganized. These relatively rare mothers may develop delusional beliefs that their baby is either cursed by the devil or specially blessed by God, that the child is dying or, alternately, has superpowers (such as speaking from the crib), or experience auditory hallucinations of voices demanding that the mother harm herself or the child. Only 0.1 to 0.2% of all women develop postpartum psychoses, but of these unfortunate few, 4% will kill their children.

The infant will need a caregiver who is well. The mother will need the help of her OB-GYN, a psychiatrist, and a social worker. A spouse and siblings will need their own support network to deal with the stresses posed by the mother and child. Everyone involved may need regular breaks simply to get away from the tension of the situation during the long process of psychological healing.

Treatment Options

New baby blues usually aren't treated at all. Postpartum depression is usually treated on an outpatient basis. Postpartum psychosis is a medical emergency requiring psychiatric hospitalization and medication.

Antidepressant medications such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine usually do not pass into breast milk in measurable amounts, although the long-term effects of trace amounts of these drugs on infants are not known. Antipsychotic and anticonvulsant medications such as valproic acid and carbamazepine definitely do pass into breast milk, and can cause severe liver damage in the baby if breastfed by the mother when taking these drugs.

See Also: Postpartum Problems Every Mom Should Know About

Sometimes it is better to forgo breastfeeding the infant so that the mother can receive treatment for depression. Any mother who has become depressed during pregnancy, or who has a a history of postpartum depression with older children, should be evaluated for treatment with antidepressants beginning immediately after the delivery of the baby. And new mothers who had difficult childhoods should be offered all the support that is available for them to minimize stress and help the happy, normal development of the child.

- Shalev, A.Y., Freedman, S., Peri, T., Brandes, D., Sahar, T., Orr, S., Pitman, R. (1998). Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry, 155. pp. 630-637.

- Soderquist, J., Wijma, B., Thorbert, G., Wijma, K. (2009). Risk factors in pregnancy for post-traumatic stress and depression after childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 16(5). pp. 672-680.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Jessica Pankratz by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/jessanick/14283762079

Your thoughts on this