Table of Contents

There are several indicators that HIV has mutated to a multiple-drug resistant form, or a HIV+ person has been infected with a new strain of the virus that is multiple-drug resistant:

- Viral load goes from undetectable to detectable. A single "blip" in viral load numbers, however, does not mean that the virus has become drug-resistant.

- Viral load fails to become undetectable during the first few months of taking a new treatment regimen.

- Viral load keeps on rising despite taking all the prescribed medications at the right time.

It's helpful to know whether you have been exposed to drug-resistant HIV as soon as you know you have the virus. Doctors can test for drug-resistance very early on, although there is always a possibility that you can have both drug-resistant HIV and a "wild type" unmutated HIV. The wild type HIV can force the mutated HIV to go into hiding, only to have it come out of hiding when drugs have brought the "normal" HIV under control.

There are two principle kinds of drug-resistance testing, genotypic and phenotypic. In genotypic testing, a lab looks for genes that indicate that certain drugs won't work. Sometimes a single gene in HIV is a sign that a specific drug won't work. If the HIV in the blood drawn from the patient has a gene called M184V, the doctor knows that the HIV is resistant to Epivir and Emtriva and it probably won't help to try those drugs. For other medications, there may be a complex pattern of genetic mutations that predict resistance, particularly resistance to protease inhibitors and nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Doctors are gaining experience in using gene testing to predict resistance to these drugs, but the method is not perfect.

Genotypic testing takes one to two weeks. A second method called phenotypic resistance testing exposes the patient's virus to actual medications and measures changes in viral load in the laboratory. This method is much more precise, but it take three to six weeks to get results.

All of this testing points doctors to first-, second-, third-, and later choices for fighting the virus. A new HIV drug, however, may entirely bypass the whole problem of multiple-drug resistance. Current HIV medications attack the virus. The new experimental medication called ibalizumab, under development by TaiMed Biologics, consists of genetically engineered antibodies. These antibodies interact directly with T-cells rather than with the virus. When these monoclonal (genetically engineered) antibodies come in contact with the receptor sites that can receive HIV, they lock out the virus and keep the cell from becoming infected.

READ Circumcision Could Lead To Better HIV Protection. Or Maybe Not.

There have been reports about ibalizumab since 2010. However, it has finally passed two clinical trials and is finally ready for large-scale testing. If the medication works in the third stage trial as well as in the first, HIV+ people will have a treatment that is taken twice a week rather than several times a day, doesn't depend on absorption through the digestive tract, isn't processed by enzymes in the liver and therefore not subject to most drug interactions, and to which HIV cannot become resistant. The FDA is treating it as an orphan drug, not really needed by people who respond to other therapies, but experts estimate that as many as 5 percent of all HIV+ people will be able to get it with medical insurance upon successful completion of the clinical trial. The majority of HIV patients, experts say, are doing fine, but this new treatment may be what is needed for those who are not. This new drug won't be an HIV cure, but it may be the next best thing.

- Reichert JM. Antibodies to Watch in 2016. MAbs. 2016. 8(2):197-204. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1125583. PMID: 26651519.

- Infographic by SteadyHealth.com

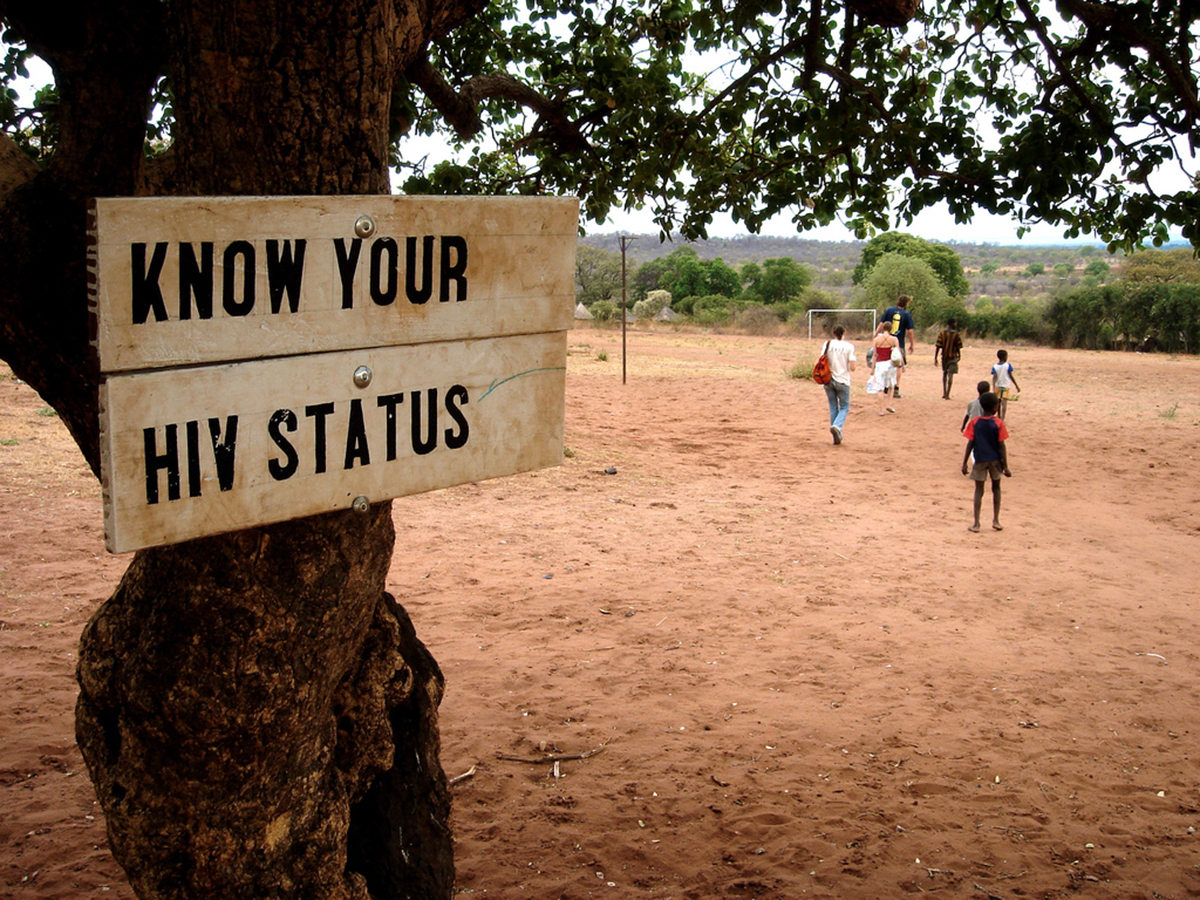

- Photo courtesy of london: www.flickr.com/photos/london/75148497/

- Infographic by SteadyHealth.com

Your thoughts on this