Cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the United States; and although overall cancer death rates have declined due to advances in medicine and emergence of novel therapies, cancer is still one of the major causes of mortality around the globe. Despite aggressive multimodality treatments which include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, deaths from aggressive cancer still persist and scientists have struggled for decades to develop more effective treatments.

In some types of cancers, the improvements were very impressive. In many others, unfortunately, the situation changed very little. New, radically different approaches for cancer treatment are still needed. One of such approaches which attracts an increasing attention is viral therapy.

Viral therapy: old strategy with huge potential

Viral therapy, or oncolytic virotherapy, as it is usually referred to in scientific and medical circles, is one of the lesser known strategies, which has been under development for over 40 years now. The concept of eliminating cancer cells by using specific viral strains dates back to 1971, when a report was published describing the effects of the Newcastle disease virus in gastric cancer, which appeared to cause tumor regression following the infection of the cancerous cells. The connection between severe viral infections and tumor regression was noticed even earlier.

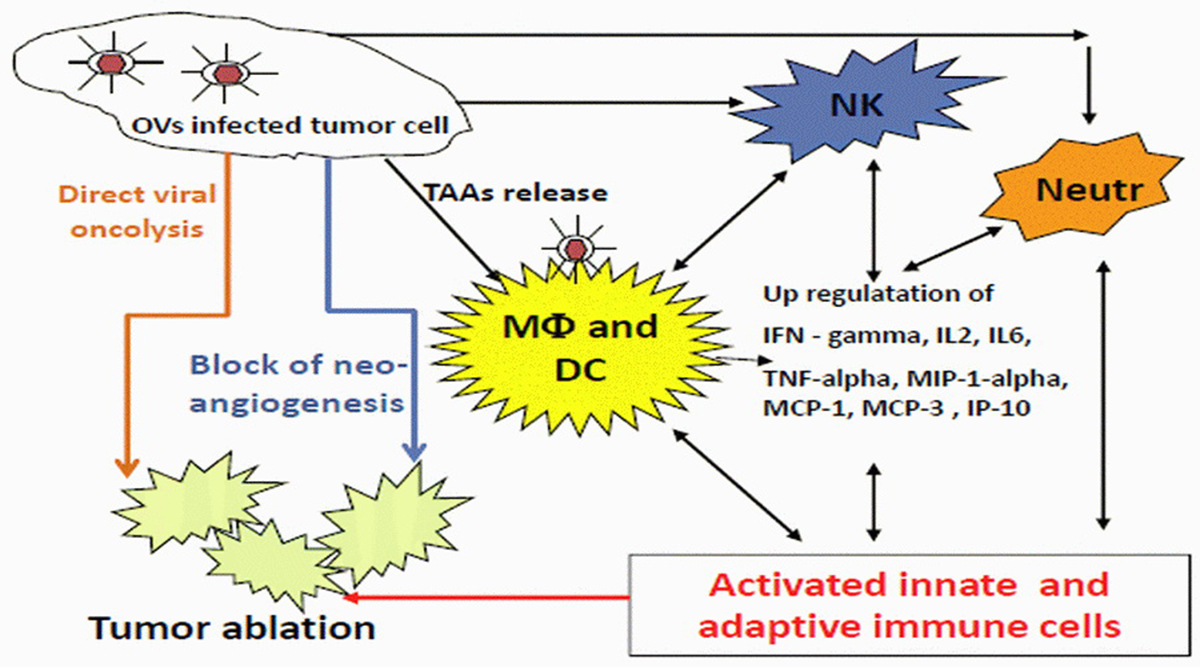

The principle underlying the action of oncolytic viruses is based on the fact that aggressive tumor cells show both impaired antiviral responses and optimal conditions for virus reproduction.

Some viruses have been artificially changed (“attenuated”) to predominantly replicate in and kill malignant cells while sparing normal tissues. Non-attenuated viruses that do not cause disease in humans can still effectively kill malignant cells in a similar fashion. Additionally, larger viruses can be armed to express immune-stimulating genes to recruit an influx of immune effector cells to further augment their therapeutic effect. Genetic manipulation of oncolytic viruses is particularly promising, as it offers much more complicated, gene-based therapeutics to be utilized to specifically target unique features of tumor cells. Therefore, these agents open up new horizons for the treatment of cancer types that commonly display poor prognosis.

See Also: Oncolytic Viruses: Future Of Cancer Therapy?

When the general idea of using viruses to treat cancer first emerged, multiple preclinical studies were carried out with both tissue cultures and rodent disease models. Later on, hundreds of cancer patients were treated with impure oncolytic virus preparations (even infected body fluids) administered by almost every imaginable route. The viruses were usually attacked by the patient’s own immune system and had little impact on tumor growth. However, in some cases the desired viral infection actually occurred and tumors regressed. However, investigations did not progress and much of the clinical studies on oncolytic therapy were halted until more recent years – mostly due to the fact that the adequate technology to carry out these investigations was not available.

Modern Science And New Era Of Oncolytic Viral Therapy

The modern era of oncolytic virotherapy, in which the genetic material of the viruses is modified so as to enhance their anti-tumor specificity, began with a 1991 publication in which a modified herpes simplex virus (HSV) with attenuated neurovirulence was shown to be active in a Murine glioblastoma model. Since that first application of virus engineering to an oncolytic HSV, the pace of clinical activities has been Renovated and has gained a lot of attention, with a lot of clinical trials.

Evidence for the efficacy of single-agent oncolytic virotherapy is limited, as only very few early phase clinical trials have been conducted. The potential efficiency is, however, supported by several positive reports. In one trial, talimogene laherparepvec, a modified oncolytic herpes simplex virus was administered by direct intratumoral injection to patients with metastatic malignant melanoma and led to complete regression of injected and even non-injected lesions in 8 of 50 treated patients.

In a second trial, an oncolytic vaccinia virus, JX594, which was similarly manipulated, was administered intratumorally to patients with non-resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Good responses were detected in three out of ten patients.

Recent clinical data look extremely promising

More recently, the report on a phase 1 trial where an engineered measles virus was used in two patients with resistant multiple myeloma was published. The results were highly promising, as both patients responded, showing reduction of both bone marrow cancer and myeloma protein.

It still remains to be seen if the disease will come back in this patient, but at the time of publication the patient was completely fine.

Over the past decade, several viruses have been translated from the laboratory to the clinic, and several more viruses are likely to be used in clinical trials in the near future. Oncolytic viruses are immensely diverse, spreading through tumors and killing tumor cells by multiple mechanisms and with different rate. Each virus has unique benefits and limitations as an oncolytic agent, which may help to determine how it is used. Because of their large size and ability to trigger an immune response, they are constrained by physical barriers and by each patient’s own immune system. Nonetheless, they can also increase the anti-tumor immunity, serving as a cancer immunotherapy. They might even be combined with drugs, radiation, monoclonal antibodies, small-molecule inhibitors, and/or other oncolytic viruses to generate increased efficacy.

See Also: Antioxidants And Anticancer Therapy: Benefits And Controversies

Overall, the field has developed rather slowly, but recent clinical trial data have been promising, and a first-in-class US approval is expected soon for talimogene laherparepvec, which is being tested in a randomized phase 3 clinical trial that has recently completed accrual. It does look like a single-shot cure for cancer is not a wild phantasy, after all!

- RUSSELL, S. J., PENG, K.-W. & BELL, J. C. 2012. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nature Biotechnology, 30, 1-13

- AURELIAN, L. 2013. Oncolytic virotherapy: the questions and the promise. Oncolytic Virotherapy, 2, 19–29

- MOEHLER, M., GOEPFERT, K., HEINRIC, B., BREITBACH, C. J., DELIC, M., GALLE, P. R. & ROMMELAERE, J. 2014. Oncolytic Virotherapy as Emerging Immunotherapeutic Modality: Potential of Parvovirus H-1. Frontiers in Oncology, 4, 92

- RUSSELL, S. J., FEDERSPIEL, M. J., PENG, K.-W., TONG, C., DINGLI, D., MORICE, W. G., LOWE, V., O'CONNOR, M. K., KYLE, R. A., LEUNG, N., BUADI, F. K., RAJKUMAR, S. V., GERTZ, M. A., LACY, M. Q. & DISPENZIERI, A. 2014. Remission of Disseminated Cancer After Systemic Oncolytic Virotherapy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Vol. 89 Iss. 5

- SMITH, T. T., ROTH, J. C., FRIEDMAN, G. K. & GILLESPIE, G. Y. 2014. Oncolytic viral therapy: targeting cancer stem cells. Oncolytic Virotherapy, 3, 21-33

- CHAI, Z., ZHANG, P., FU, F., ZHANG, X., LIU, Y., HU, L. & LI1, X. 2014. Oncolytic therapy of a recombinant Newcastle disease virus D90 strain for lung cancer. Virology Journal, 11, 84.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of AJ Cann by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/ajc1/14194434111

Your thoughts on this