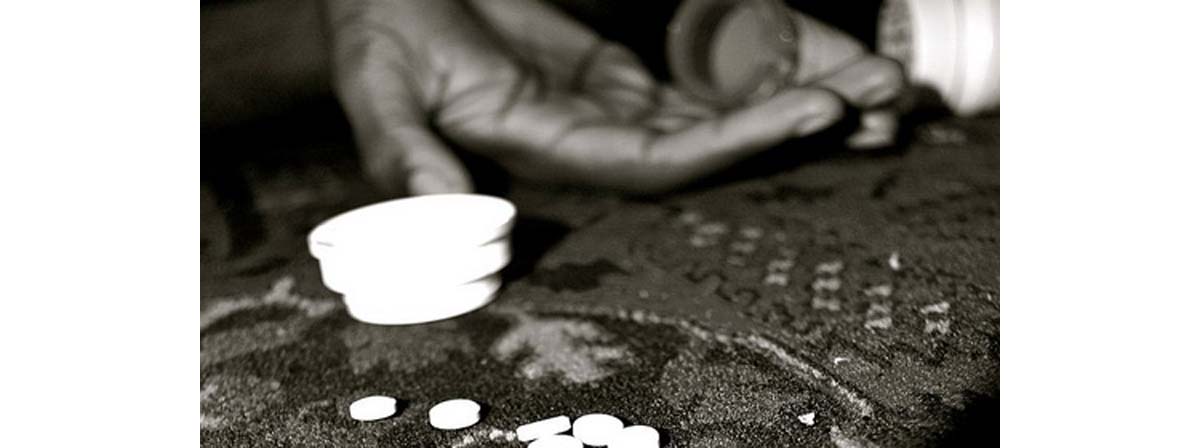

An astonishing number of famous people have died of both accidental and intentional drug overdoses. The accidental death of 31-year-old Canadian actor Corey Monteith from a combination of heroin and alcohol is just one of many examples. Before that, 29-year-old Australian actor Heath Ledger died after taking a fatal combination of the prescription painkillers alprazolam, diazepam, doxylamine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and temazepam, leaving a three-year-old daughter behind.

And just since the year 2000, the roster of deaths of famous people from overdoses of recreational and prescription drugs has included:

- Pop singer Michael Jackson, of a combination of physician-administered drugs and tranquilizers,

- Rapper Michael Larsen, aka Eyedea, of an accidental overdose of opiates,

- Painter Thomas Kinkade, of a combination of alcohol and tranquilizers,

- Wrestler Chris Kanyon, of an overdose of antidepressants,

- Rapper Russell Jones, of a combination of cocaine and tranquilizers,

- Playboy Playmate Jeniffer Lyn Jones, of a heroin overdose,

- Surfer Andy Irons, of a combination of cocaine, methamphetamines, and tranquilizers,

- Skate boarder Harold Hunter, of a cocaine-induced heart attack at the age of 32.

Drug overdoses tend to kill people in the prime of their lives. One medical examiner interviewed during the writing of this article noted that people who intentionally kill themselves by taking massive doses of drugs usually don't leave a note, and the medical literature suggests that people who succeed in killing themselves by taking an overdose of drugs who do leave a note often express anger. They might, for example, say, "I hope this makes you happy!", and they may report incidents of abuse by people close to them. People who don't succeed in their suicide attempt after leaving a note tend to be far more likely to warn survivors of possible dangers (for instance, "careful, cyanide gas in the bedroom"), are far more likely to report that they just couldn't go on, and are also far less likely to attempt to use medications or drugs as the means of their death.

If you find someone who is comatose and who has left a note, the chances of successful intervention are far greater than if you find someone who has taken "something" and not left a note. And if you know that a person in your life is angry and suicidal, chances are that if they indicate that they will take their lives, they mean business. But what can you do if someone is talking about suicide, or if you find evidence that someone you know and love has already taken steps to end their own life by taking an overdose of drugs?

How to Respond to Suicide Hints, Threats, and Attempts

Just about anyone who hints of or threatens suicide is profoundly ill, even if the threat of suicide is primarily an attempt to gain attention (which does not have to be a negative thing in this context, since they clearly need assistance), to access treatment, or to avoid abandonment. People who have a psychiatric disorder known as borderline personality disorder, in which they experience real or imagined abandonment, are given to dramatic demonstrations of their emotional need which may include attempts of suicide.

A significant percentage of people who have this psychiatric condition actually do eventually commit suicide, so professional intervention — the difficulties associated with borderline personality disorder are not something a friend can fix — is required for threats of suicide and even hints of suicide even if they seem to be "drama."

Modern Pain Relievers Are Extremely Potent

One thing to take into account is that the simple reality of modern antidepressants and pain relievers is that they can be very potent. Someone who is trying to relieve pain by taking multiple pain prescriptions (Heath Ledger's alprazolam, diazepam, doxylamine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and temazepam, for instance) runs a real risk of death from respiratory or cardiac arrest. And it is death from taking too many prescription medications that is more likely to be accidental. In these cases, the person wanted to feel better, not to end their life.

If a doctor prescribes it, the user reasons, the combination of drugs has to be OK. The problem occurs when people start seeing multiple doctors to get multiple prescriptions for multiple pain relievers. What a friend can do is to be just a little nosy, and to ask if there isn't a better way to get the relief from pain or anxiety that is needed other than taking more and more pills. Even if the person reacts in a hostile way, which is likely, you may get them to think.

Street Drugs Have Unpredictable Effects

Street drugs are a more difficult problem. The people who refine cocaine and heroin don't run quality standards in their labs. Sometimes a batch of a drug won't be "cut." It will be full strength. Medical examiners will see multiple cases of drug overdoses in just a few days and pass on the word to police departments, and chiefs of police may even put out the word that people are dying of drug overdoses so that the drug dealers hear it. Drug dealers may not be pharmacologically astute, but they do realize that uncut drugs cost them money and dead people don't buy their drugs. When a drug dealer watches the local evening news and sees multiple reports of drug overdoses, they check their supplies.

Drug Stories on the Evening News Are Sometimes There for a Reason

And if you have a friend who uses street drugs, you should keep up with the evening news, too. "I know my dealer" isn't a guarantee that a drug will be safe. Friends usually can't persuade friends to give up their drug habits. But friends can warn friends when bad drugs are on the street, and ask them to be careful, avoid being the friend who provides them alcohol, and make a point of being there when they are needed to call for emergency help.

The simple truth is that you cannot always prevent a friend's drug overdose — but you can try, and sometimes, you will succeed.

- Dowell D, Kunins HV, Farley TA. Opioid analgesics--risky drugs, not risky patients. JAMA. 2013 Jun 5. 309(21):2219-20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5794. PMID: 23700072.

- Pestian JP, Matykiewicz P, Linn-Gust M. What's In a Note: Construction of a Suicide Note Corpus. Biomed Inform Insights. 2012. 5:1-6. doi: 10.4137/BII.S10213. Epub 2012 Nov 5. PMID: 23170067 [PubMed].

- Photo courtesy of Sam Metsfan by Wikimedia Commons : commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DrugOverdose.jpg

- Photo courtesy of Brittany Randolph by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/celinesphotographer/375123991/

Your thoughts on this