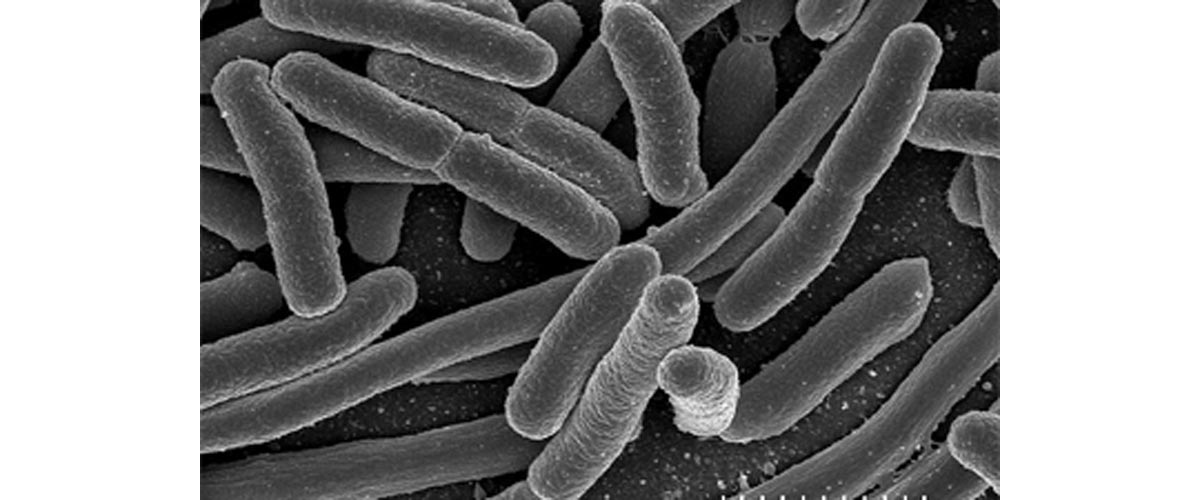

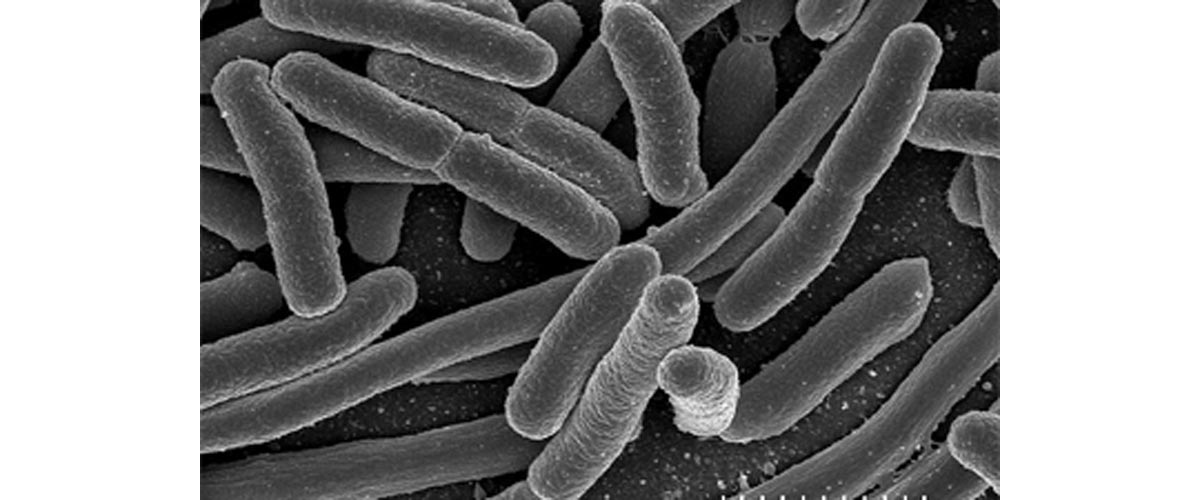

For over a week the lead stories on the news have concerned the outbreak of E. coli infection centered in Germany. As this article is being written, a relatively uncommon strain of one of the world's most common bacteria has killed 22 people.

...put 600 people in intensive care units, and sickened over 2,000 more.

First mistakenly linked to Spanish cucumbers, the outbreak is now being blamed on failures of sanitation at a German producer of bean sprouts. But is this outbreak a reason to panic? Let's take a hard look at the facts.

Over just two weeks, current outbreak of E. coli in Germany has affected nearly 3,000 people, but this is hardly the first E. coli outbreak in the European Union. Last year, at least 3,500 people in the European Union were treated for E. coli infections confirmed by laboratory analysis. Some countries, like Denmark and Ireland, are very vigilant in tracking E. coli infections, while other countries are not. European epidemiologists believe only a small number of infections were actually diagnosed.

Over just two weeks, current outbreak of E. coli in Germany has affected nearly 3,000 people, but this is hardly the first E. coli outbreak in the European Union. Last year, at least 3,500 people in the European Union were treated for E. coli infections confirmed by laboratory analysis. Some countries, like Denmark and Ireland, are very vigilant in tracking E. coli infections, while other countries are not. European epidemiologists believe only a small number of infections were actually diagnosed.

The United States has been tracking E. coli infections among Americans since 1967. In 2010, there were 96,534 known cases of E. coli requiring medical treatment, causing 31 deaths. Epidemiologists estimate that there may actually have been as many as 750,000 people who became sick after E. coli infections, but since they were being treated for other medical problems before they were sickened by E. coli, the infection was not reported to public health officials.

That's a lot more people than have been sickened by the outbreak in Germany. Why is that a much bigger problem with E. coli didn't make the news?

This is beneficial for the bacterium. Breaking down red blood cells and causing bloody diarrhea spreads the organism to other hosts. The difference between O157:H7 that we have been hearing about for years and O104:H4 that is in the current outbreak is that the new E. coli bug also has an enhanced ability to stick to the lining of the intestines. It's harder to flush away.

Some commentators say that they only way the current strain of bacteria could have developed resistant to nine different antibiotics is that some mad scientist or terrorist cultivated this strain of E. coli, exposing it to all nine antibiotics at once.

That's just not the way antibiotic resistance works. Bacteria develop resistance by mutation, and then if they survive all the other things that can kill bacteria, they can physically transfer genetic material to other microbes in a kind of "bacterial sex". Most mutations don't have anything to do with antibiotics, and they are just as likely to kill the bacterium as they are to transform it into a super-bug.

For things to happen the way the conspiracy theorists suggest, at least one bacterium would have had nine mutations at the same time, and then it would have to been identified from trillions of other bacteria, and then it would have had to been cultures and sneaked into a bean sprout factory in the dead of night. Utterly impossible? No. Very improbable? Yes.

And some websites also claim that pharmaceutical companies bioengineered the bacterium so they could sell more drugs. Well, if you are going to bioengineer a microorganism to make people sick so they have to buy your drugs, maybe you should create a microbe for which you have a medication. German doctors observed very quickly that giving people infected with O104:H4 antibiotics made them sicker, not better.

There are no drugs to be bought and no profits to be made by the drug companies as the result of this E. coli outbreak. Only the colloidal silver makers who pay for the articles about drug company plots to make the world sick stand to profit from people's fear and suffering. But I personally don't believe they created the bacterium, either.

Anything you can do to stay healthy during an outbreak of E. coli is something you should do all the time. The steps to take to prevent E. coli infection apply whether there is a "superbug" going around or not.

By washing your hands before you use the toilet, you avoid transferring germs from the outside world to your private parts. But washing your hands after you use the toilet, you avoid transferring your own germs to someone else.

By washing your hands before you use the toilet, you avoid transferring germs from the outside world to your private parts. But washing your hands after you use the toilet, you avoid transferring your own germs to someone else.

Seeds have to be soaked in water to grow sprouts, and the warm temperatures and constant humidity give E. coli many opportunities to grow. Simply washing sprouts before you eat them, and keeping them refrigerated, will lower the number of bacteria on the sprouts to a smaller number that your body can eliminate with stomach acids.

Bitter salad greens trigger a reflex that increases production of stomach acid.

Eat foods made with chilis or curries. Hot peppers and spices used to make curries fight foodborne infections.

Keep the statistics about E. coli in perspective. Every year, just in the United States, up to 750,000 people get E. coli infections. That means that every year, just in the United States, at least 308,000,000 people don't get E. coli infections.

Your risk of E. coli infection is very small, but your risks from not getting enough vegetables and fruit in your diet are very large. Take reasonable precautions and keep your hands and your kitchen clean, and then eat the foods that are good for you and that you enjoy!

First mistakenly linked to Spanish cucumbers, the outbreak is now being blamed on failures of sanitation at a German producer of bean sprouts. But is this outbreak a reason to panic? Let's take a hard look at the facts.

Foodborne Infections Probably More Common than You Think

The United States has been tracking E. coli infections among Americans since 1967. In 2010, there were 96,534 known cases of E. coli requiring medical treatment, causing 31 deaths. Epidemiologists estimate that there may actually have been as many as 750,000 people who became sick after E. coli infections, but since they were being treated for other medical problems before they were sickened by E. coli, the infection was not reported to public health officials.

That's a lot more people than have been sickened by the outbreak in Germany. Why is that a much bigger problem with E. coli didn't make the news?

Latest Strain Especially Toxic

The story of the recent outbreak in Germany has certain newsworthy scary features. Like the O157:H7 strain that is involved in most serious E. coli infections in the USA, the German E. coli, which is known as O104:H4, generates a toxin that can break down red blood cells.This is beneficial for the bacterium. Breaking down red blood cells and causing bloody diarrhea spreads the organism to other hosts. The difference between O157:H7 that we have been hearing about for years and O104:H4 that is in the current outbreak is that the new E. coli bug also has an enhanced ability to stick to the lining of the intestines. It's harder to flush away.

Was This Outbreak Created in a Terrorist Lab?

Some websites—which conveniently also sell you their natural product to fight the infection—claim that this strain of E. coli is new and had to have been created in a lab in Germany. It's not new. It wasn't created in a lab. It was identified in Korea five years ago.Some commentators say that they only way the current strain of bacteria could have developed resistant to nine different antibiotics is that some mad scientist or terrorist cultivated this strain of E. coli, exposing it to all nine antibiotics at once.

That's just not the way antibiotic resistance works. Bacteria develop resistance by mutation, and then if they survive all the other things that can kill bacteria, they can physically transfer genetic material to other microbes in a kind of "bacterial sex". Most mutations don't have anything to do with antibiotics, and they are just as likely to kill the bacterium as they are to transform it into a super-bug.

For things to happen the way the conspiracy theorists suggest, at least one bacterium would have had nine mutations at the same time, and then it would have to been identified from trillions of other bacteria, and then it would have had to been cultures and sneaked into a bean sprout factory in the dead of night. Utterly impossible? No. Very improbable? Yes.

And some websites also claim that pharmaceutical companies bioengineered the bacterium so they could sell more drugs. Well, if you are going to bioengineer a microorganism to make people sick so they have to buy your drugs, maybe you should create a microbe for which you have a medication. German doctors observed very quickly that giving people infected with O104:H4 antibiotics made them sicker, not better.

There are no drugs to be bought and no profits to be made by the drug companies as the result of this E. coli outbreak. Only the colloidal silver makers who pay for the articles about drug company plots to make the world sick stand to profit from people's fear and suffering. But I personally don't believe they created the bacterium, either.

Ten Things You Can Do to Stay Healthy During an E. coli Outbreak

Anything you can do to stay healthy during an outbreak of E. coli is something you should do all the time. The steps to take to prevent E. coli infection apply whether there is a "superbug" going around or not.

1. Wash your hands before and after you use the toilet

By washing your hands before you use the toilet, you avoid transferring germs from the outside world to your private parts. But washing your hands after you use the toilet, you avoid transferring your own germs to someone else.

By washing your hands before you use the toilet, you avoid transferring germs from the outside world to your private parts. But washing your hands after you use the toilet, you avoid transferring your own germs to someone else.2. Eat your sprouts cooked, or make sure they have been washed

The latest E. coli outbreak seems to have originated at a facility that grew bean sprouts. Another E. coli outbreak in Japan, sickening over 8,000 people in 1996, was traced back to radish sprouts. A real-life Hindu terrorist organization based in the tiny town of Antelope, Oregon, of all places, sickened hundreds of people by placing intentionally contaminated sprouts on a salad bar in 1982.Seeds have to be soaked in water to grow sprouts, and the warm temperatures and constant humidity give E. coli many opportunities to grow. Simply washing sprouts before you eat them, and keeping them refrigerated, will lower the number of bacteria on the sprouts to a smaller number that your body can eliminate with stomach acids.

3. Don't take antacids before you eat raw vegetables or raw or rare meat or eggs

Your body's first line of defense against foodborne bacteria is stomach acid. If you have to take antacids or medications for gastroesophageal reflux disease, then don't eat raw foods.4. Don't take Pepto-Bismol or Lomotil to prevent foodborne infection

Diarrhea is your body's way of eliminating toxic bacteria. If you stop diarrhea before it starts, you increase your chances of infection rather than decreasing them.5. Buy a variety of foods from a variety of sources

E. coli outbreaks usually emanate from a single location. If you buy a variety of fruits and vegetables from a variety of sources, your chances of getting a dose of bacteria too large for your digestive tract to handle decrease.6. Add vinegar-based dressings to your salads

Vinegar slows down the passage of food through your digestive tract, giving your stomach acid more opportunity to dissolve E. coli bacteria before they can cause infection.7. Eat foods cultured with Lactobacillus

"Friendly bacteria" occupy spaces on the lining of the intestines so that they cannot be colonized by infectious E. coli. You can get Lactobacillus from kimchi, sauerkraut, yogurts of all kinds, and probiotic supplements.

8. Start your meal with a small amount of a bitter food

Bitter salad greens trigger a reflex that increases production of stomach acid.

9. Think South of the Border

Eat foods made with chilis or curries. Hot peppers and spices used to make curries fight foodborne infections.

10. Keep on eating healthy food

Keep the statistics about E. coli in perspective. Every year, just in the United States, up to 750,000 people get E. coli infections. That means that every year, just in the United States, at least 308,000,000 people don't get E. coli infections.Your risk of E. coli infection is very small, but your risks from not getting enough vegetables and fruit in your diet are very large. Take reasonable precautions and keep your hands and your kitchen clean, and then eat the foods that are good for you and that you enjoy!

- Bae WK, Lee YK, Cho MS, Ma SK, Kim SW, Kim NH, Choi KC. A case of hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Escherichia coli O104:H4. Yonsei Med J. 2006 Jun 30,47(3):437-9

- Elisabeth Rosenthal, "Elusive Explanations for an E. coli Outbreak," New York Times, 7 June 2011.