By now, just about everyone has heard of the "cholesterol myth." Dozens of natural health commentators, research scientists, and a few doctors have published articles and books on the simple fact that cholesterol doesn't, all by itself, cause heart disease. And there is a lot of room to believe that the common understanding of cholesterol is just plain wrong.

A Fallacious Understanding of Cholesterol Originating in the 1950's

The common misconception of the role of cholesterol in heart disease originated in autopsies of American soldiers who died in the Korean War. Many of the young men killed in battle were found to have advanced coronary artery disease. They had cholesterol-laden plaques that would have soon killed them had they not died on the front.

To the minds of cholesterol researchers of the time, such as the increasingly infamous Ancel Keys, this could only mean one thing. Even "healthy" youth had arteries clogged with cholesterol. The damage caused by cholesterol could start as early as age 18, and the only thing to do was to eat less meat.

The 1950's-era cholesterol researchers, however, overlooked a very important explanation of the American troops' deaths. The soldiers were killed by bullets and grenades and rockets, not by heart disease. They simply could not run as fast as their comrades and they were more likely to fall on the battlefield. Whether the surviving troops had severe atherosclerosis, mild atherosclerosis, or no atherosclerosis, or whether they had high cholesterol, low cholesterol, or "healthy" cholesterol was not known. Nor did researchers know the relationship between the amount of cholesterol in food and the amount of cholesterol in the bloodstream, or how it was deposited into plaques.

A Fallacious Understanding of Cholesterol Originating in the 1990's

If you fast-forward cholesterol research to the 1990's, you begin to see numerous examples of how the accepted theory of cholesterol and heart disease just couldn't be right. Most studies found that the "average" cholesterol level of people who had heart attacks was just 150-160 mg/dl, meaning that most people who had severe heart disease not only didn't have high cholesterol levels, they likely in fact had low cholesterol.

Studies of cholesterol-lowering drugs shockingly showed that getting total cholesterol levels down did not reduce the risk of dying from heart disease, or reduced the risk of dying from heart disease by increased the risk of dying from other causes. The largest study that found a benefit from cholesterol-lowing statin drugs, the Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study, conducted in San Antonio, Texas, found that taking a statin drug for five years really did lower the risk of a "coronary event," from about 3% to about 2% in the healthy people in the study.

From this and mountains of other evidence, some critics came to believe that cholesterol doesn't really matter, but that is wrong, too. Cholesterol does matter to cardiovascular health, but it is a very specific kind of cholesterol called lipoprotein A, or Lp(a).

Lp(a), The Cholesterol That Makes A Difference In Cardiovascular Health

It turns out, as researchers know now, that all cholesterol is not created equal. The thing that is important to understand about cholesterol in the bloodstream is that, as a "fat," it would not be soluble in the fluid of the bloodstream except it is attached to protein coat that is soluble in the bloodstream.

The protein layer around a "nugget" of cholesterol is known as lipoprotein, and the size of the balloon-like protein coating around cholesterol determines how it interacts with tissues in the body:

- Very large pieces of cholesterol are relatively light. They are known as very low-density lipoprotein or VLDL cholesterol.

- Slightly smaller pieces of cholesterol are also slightly denser. This next size of cholesterol is known as low-density liporprotein or LDL cholesterol, the kind of cholesterol that has widely become known as the "bad cholesterol".

- The smallest pieces of cholesterol are also the densest. The size of cholesterol is known as high-density lipoprotein or HDL cholesterol.

Cholesterol is not a toxic substance. Every cell in the human body uses it to make its protective lining so that its contents do not dissolve into the bloodstream. Some white blood cells also use it as fuel. The size of the cholesterol particle determines where it is used. VLDL and LDL cholesterol tend to be used in muscle tissue, while HDL cholesterol concentrates in the liver.

How Cholesterol Becomes "Bad"

Cholesterol is only a bad thing when it gets stuck in the linings of blood vessels. Not every size of cholesterol particle, however, can get stuck in the lining of a blood vessel.

VLDL cholesterol is too large to lodge in the lining of a blood vessel. HDL cholesterol is too small. Even the larger pieces of LDL cholesterol are harmless in the bloodstream. Only the not-quite-HDL sized Lp(a) cholesterol, which is a kind of LDL cholesterol, is the problem.

And even this specific form of cholesterol does not form a plaque until it is consumed by a kind of white blood cell known as a macrophage, the macrophage sends out a signal to other macrophages known as macrophage migration factor, and the whole mass calcifies in place, typically over a period of 10 to 20 years. These same white blood cells play a role in fighting infections and even cancer, because they target any cell that doesn't seem to belong in your body.

The "Cholesterol Myth" and What You Need to Do About It

Since not every kind of cholesterol can cause damage to the arteries, total cholesterol, the number most of us know, doesn't have a lot to do with the risk of heart disease. Even the LDL cholesterol reading doesn't give any direct, actionable information on cardiovascular risk. And doctors usually don't order the test for the Lp(a), also known as lipoprotein A-1, that actually does predict the risk of heart disease. As a result it is possible to have "high cholesterol" and never have a heart attack, and it is possible to have "low cholesterol" and have a heart attack at an early age.

Not only do doctors not typically measure the kind of cholesterol that actually causes heart disease, they don't treat it, either. However, this does not mean you should throw your statin drugs away.

Statin medications don't just lower cholesterol. (They do lower cholesterol, although this isn't their main benefit.) They also prevent inflammation. If you already have atherosclerosis, taking a statin medication will help prevent the rupture of existing plaques that attracts clots and closes arteries, causing heart attack or stroke.

The problem is, just because you have "good cholesterol numbers," you don't have any way of knowing from that number whether or not you already have cardiovascular disease. The real solution is to ask your physician to test for Lp(a), and prescribe a statin medication, or not, on the basis of that number. If you can't have that test, however, the now-standard prescription for statin drugs is, regrettably, a good idea for most people.

Since this article was first written, tests for LP(a) cholesterol have thankfully become more common. Your doctor may recommend an LP(a) cholesterol test if you have a history of heart disease, symptoms of heart disease, or diagnosed heart disease despite seemingly normal cholesterol levels. If your doctor has not advised this test, you can absolutely ask for it if you have grounds to justify it.

- Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM Jr. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998 May 27. 279(20):1615-22.

- Riches K, Porter KE. LIpoprotein (a): Cellular Effects and Molecular Mechanisms. Cholesterol. 2012

- 2012:923289. Epub 2012 Sep 6.

- von Dryander M, Fischer S, Passauer J, Müller G, Bornstein SR, Julius U. Differences in the atherogenic risk of patients treated by lipoprotein apheresis according to their lipid pattern. Atheroscler Suppl. 2013 Jan.14(1):39-44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2012.10.005.

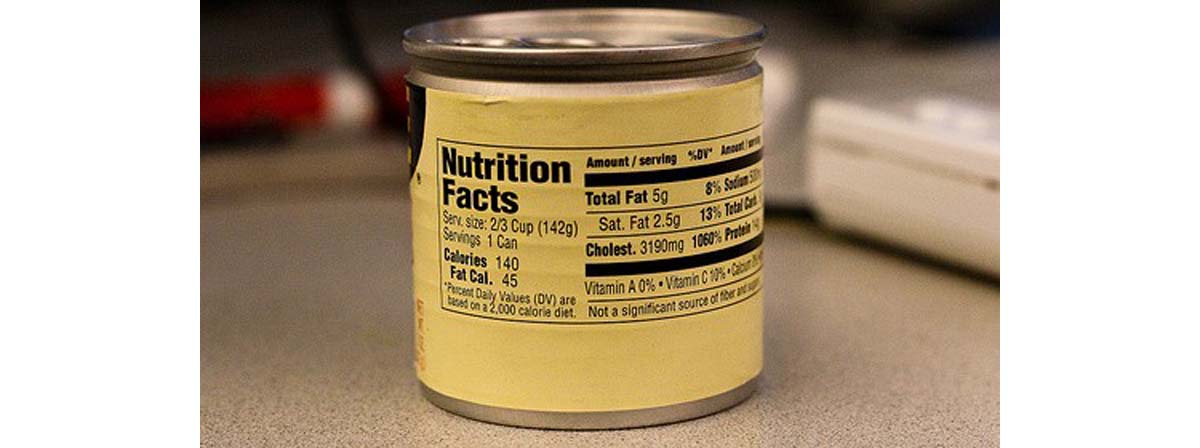

- Photo courtesy of kulor on Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/kulor/3354272606

Your thoughts on this