Coffee is the most consumed of all non-water beverages in the world (I know what you are thinking; no it’s actually not alcohol!).

And, we all know that caffeine is one of the main reasons for our drinking coffee. Although caffeine is contained in foods as well, more often than not we turn to caffeinated beverages like coffee, tea (to a lesser extent) and energy drinks for our daily dose of caffeine.

So, what is it about caffeine that endears it so much to us all? Well, let’s find out! But, before we go into the nitty-gritty of what makes caffeine ‘special’, let us have a look at what caffeine is and indeed, what caffeine does to our minds and bodies.

What is caffeine?

Chemically speaking, caffeine is 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine.

Once we sip it, this caffeine gets absorbed through our gastrointestinal tracts (stomach and intestines) within a matter of minutes. After it's absorbed, the caffeine you slurped down moves rapidly through cell membranes and tissues, exerting its action. Even the blood brain barrier isn't able to stop caffeine; caffeine, thus effortlessly enters our brain tissue and exerts a prominent action there.

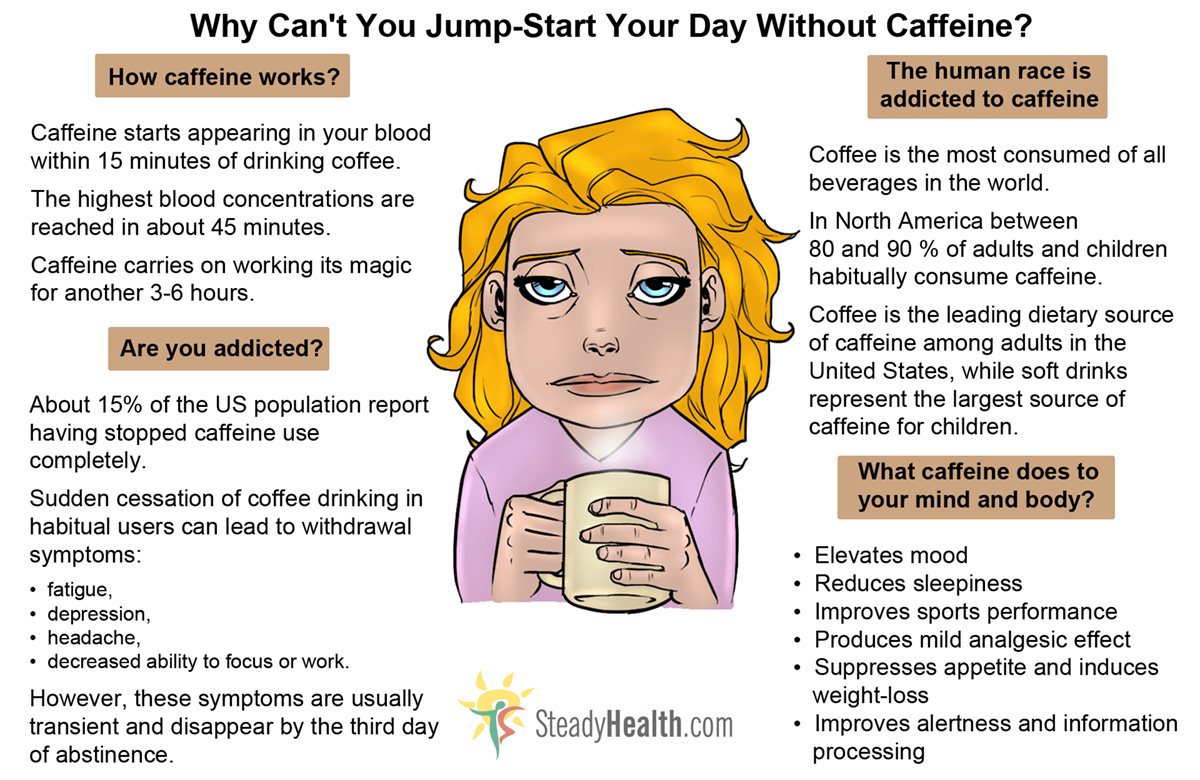

According to some estimates, caffeine starts appearing in our blood within 15 minutes of drinking coffee; the highest blood concentrations are reached in about 45 minutes. And caffeine carries on working its magic for another 3 to 6 hours after that.

Pharmacologically, caffeine is an adenosine receptor antagonist. Adenosine is a chemical that depresses the release of excitatory neurotransmitters – noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, glutamine and GABA. This action is mediated through the stimulation of adenosine receptors.

Blockage of the adenosine receptors by caffeine, therefore, leads to increased release of the above mentioned excitatory neurotransmitters. Caffeine can therefore be said to possess a central nervous system stimulant action.

What does caffeine do to our minds and bodies?

Here are some wonderful things – discussed in detail – that caffeine can do for you:

- Coffee elevates your mood: The effects of caffeine on the mood have been extensively studied in humans. There is evidence to suggest that lower doses of caffeine (20-200 mg) may have a positive effect on your mood. ‘Energetic’, ‘imaginative’, ‘confident’ and ‘alert’ are some of the terms that coffee drinkers use to describe the effects of caffeine. Additionally, improved motivation and an enhanced ability to concentrate are also reported. An interesting observation is that caffeine – owing to its mood elevating abilities – has the potential to reduce the severity of depression and the risk of suicide, if only for a short time.

- Coffee reduces sleepiness and improves alertness and information processing: Not only does caffeine elevate your mood but it can also reduce sleepiness and keep you awake – even when it's used in a doses as small as 50 mg per day. Caffeine is apparently believed to cause increase in the rate of cerebral metabolism. Regular coffee consumers report ‘better workplace performance’ and reduced reaction times. Likewise, caffeine improves self esteem, confidence and socializing as well. Furthermore, anecdotal evidence suggests that coffee drinking works well to improve focus when students use it during times of examination. Similarly, the usefulness of caffeine when used by elite armed forces – for producing wakefulness and alertness – has also been proven.

- Coffee improves sports performance: It has long been suspected that caffeine, when taken in low-moderate doses, improves sports performance especially in trained athletes. Caffeine is of benefit in extended, exhaustive exercise situations like ultra-endurance events and in high-intensity exercises such as sprints associated with football and rugby. Furthermore, in a very interesting finding, Stuart et. al. reported that caffeine improved the skill levels (ball control) of athletes under match conditions as well as in training (Stuart et al., 2005). Enhanced mental focus, reduced reaction times, improved lean muscle mass (as discussed in the subsequent section), and efficient utilization of energy substrates are some of the mechanisms thought to be responsible for caffeine’s performance-enhancing abilities. Apparently, caffeine is so efficient that four cups of ‘pre-match’ black coffee has almost become a norm in all elite level soccer tournaments. You'll find caffeine, in large doses, in preworkout supplements for this precise reason.

- Coffee suppresses your appetite and induces weight-loss: Like most central nervous system stimulants, caffeine too suppresses appetite and reduces daily calorie intake. Although, how it does so is not known, caffeine seems to be as effective as amphetamines in causing appetite suppression . Interestingly, rather than reducing the portion size of individual meals, caffeine has been shown to reduce meal frequency. Another aspect of caffeine’s weight-reducing effect – or better yet, its ‘body composition’ improving effect – is its ability to alter substrate use. Whereas normally, the body relies on use of carbohydrate for producing energy, consumption of coffee shifts the balance in favor of fats. Utilization of fatty acids over carbs, especially when exercising leads to loss of body fat. Thus, decreased reliance on glycogen breakdown and increased dependence on fatty acid metabolism to provide energy to the exercising muscles is responsible for improved body composition.

A combined result of suppression of appetite and preferential burning of fat over carbs is what makes caffeine a much sought-after ingredient in most ‘fat-loss’ or ‘ergogenic’ formulations.

- Coffee produces analgesia: Caffeine produces a mild analgesic effect, which in layman's terms means it's a bit of a painkiller. In combination with its mood-elevating effects, caffeine may prove to be quite an effective painkiller. Caffeine is commercially available in combination with acetaminophen (paracetamol); this boosts the efficacy of either drug to produce profound analgesia. It's especially great when you try to stop a headache in its tracks.

Is Caffeine Safe For Consumption?

Despite caffeine being a ‘behaviorally active’ substance, it is seldom associated with adverse health events – even in cases of long-term use in moderately high doses.

Although, it is ingrained in the popular psyche that caffeine causes anxiety, there isn't much scientific evidence that it does so. Even in patients with pre-existing anxiety, caffeine doesn't seem to add to the anxious state . Having said that, very high doses of caffeine (1000 mg or more) do seem to induce anxiety and jitteriness.

The association between coffee consumption and psychiatric disorders – similar to anxiety – has not been proven either. However, it has been reported that caffeine may worsen the severity of schizophrenia symptoms in diagnosed individuals.

Depression, on the other hand, as would be suspected is affected favorably by drinking coffee as caffeine has a small but important mood lifting effect.

Caffeine dependence and withdrawal symptoms

However, these symptoms are usually transient and disappear by the third day of abstinence.

In general, caffeine when consumed in low to moderate doses – especially in the form of coffee seems to be generally safe. No wonder then, government agencies have rarely put restrictions on the use of caffeine. Also, even though caffeine has been shown to enhance sports performance, WADA – in 2004 – removed caffeine from its doping list. This is so because caffeine does not seem to undermine health – one of the main reasons cited for banning a substance.

An interesting fact is that while previously, researchers tended to brand caffeine a ‘potential drug of abuse’, the recent scientific view is that caffeine is a ‘model drug of abuse’ – meaning that if you were to ever get addicted to a substance, it better be caffeine rather than some other sinister drug!

Take home message

Caffeine seems to be quite an effective ‘performance enhancing’ aid – weather at your place of work or on the field. Furthermore, it seems to elevate mood, reduce reaction times and improve cognition. It is, therefore, quite understandable that we just can’t jump-start our day without a cup of coffee.

- Carrillo, J. A. & Benitez, J. (2000). Clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions between dietary caffeine and medications. Clin Pharmacokinet., 39, 127-153

- Del, C. J., Munoz, G., & Munoz-Guerra, J. (2011). Prevalence of caffeine use in elite athletes following its removal from the World Anti-Doping Agency list of banned substances. Appl.Physiol Nutr.Metab, 36, 555-561

- Eaton, W. W. & McLeod, J. (1984). Consumption of coffee or tea and symptoms of anxiety. Am J Public Health, 74, 66-68

- Erickson, M. A., Schwarzkopf, R. J., & McKenzie, R. D. (1987). Effects of caffeine, fructose, and glucose ingestion on muscle glycogen utilization during exercise. Med Sci.Sports Exerc., 19, 579-583

- Foltin, R. W., Kelly, T. H., & Fischman, M. W. (1995). Effect of amphetamine on human macronutrient intake. Physiol Behav., 58, 899-907

- Fredholm, B. B. (1995). Astra Award Lecture. Adenosine, adenosine receptors and the actions of caffeine. Pharmacol.Toxicol., 76, 93-101

- Fredholm, B. B., Battig, K., Holmen, J., Nehlig, A., & Zvartau, E. E. (1999). Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol.Rev, 51, 83-133

- Gilliland, K. & Bullock, W. (1983). Caffeine: a potential drug of abuse. Adv.Alcohol Subst.Abuse, 3, 53-73

- Goldstein, A. & Wallace, M. E. (1997). Caffeine dependence in schoolchildren? Exp.Clin Psychopharmacol., 5, 388-392

- Goldstein, E. R., Ziegenfuss, T., Kalman, D., Kreider, R., Campbell, B., Wilborn, C. et al. (2010). International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr., 7, 5

- Griffiths, R. R., Evans, S. M., Heishman, S. J., Preston, K. L., Sannerud, C. A., Wolf, B. et al. (1990). Low-dose caffeine discrimination in humans. J Pharmacol.Exp.Ther, 252, 970-978

- Griffiths, R. R., Holtzman, S. G., Daly, J. W., Hughes, J. R., Evans, S. M., & Strain, E. C. (1996). Caffeine: a model drug of abuse. NIDA Res.Monogr, 162, 73-75

- Harland, B. F. (2000). Caffeine and nutrition. Nutrition, 16, 522-526

- Holtzman, S. G. (1990). Caffeine as a model drug of abuse. Trends Pharmacol.Sci., 11, 355-356

- Ivy, J. L., Costill, D. L., Fink, W. J., & Lower, R. W. (1979). Influence of caffeine and carbohydrate feedings on endurance performance. Med Sci.Sports, 11, 6-11

- Kawachi, I., Willett, W. C., Colditz, G. A., Stampfer, M. J., & Speizer, F. E. (1996). A prospective study of coffee drinking and suicide in women. Arch.Intern.Med, 156, 521-525

- Lieberman, H. R., Wurtman, R. J., Emde, G. G., & Coviella, I. L. (1987). The effects of caffeine and aspirin on mood and performance. J Clin Psychopharmacol., 7, 315-320

- McArdle, W., Katch, F., & Katch, V. (2007). Energy, Nutrition & Human Performance. In Exercise Physiology ( Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins

- McCall, A. L., Millington, W. R., & Wurtman, R. J. (1982). Blood-brain barrier transport of caffeine: dose-related restriction of adenine transport. Life Sci., 31, 2709-2715.

- Mikkelsen, E. J. (1978). Caffeine and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry, 39, 732-736.

- Myers, D. E., Shaikh, Z., & Zullo, T. G. (1997). Hypoalgesic effect of caffeine in experimental ischemic muscle contraction pain. Headache, 37, 654-658.

- Powers, S. & Howley, E. (2004). Theory and application to fitness and performance. In Exercise Physiology ( New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Robertson, D., Frolich, J. C., Carr, R. K., Watson, J. T., Hollifield, J. W., Shand, D. G. et al. (1978). Effects of caffeine on plasma renin activity, catecholamines and blood pressure. N Engl J Med, 298, 181-186.

- Schneiker, K. T., Bishop, D., Dawson, B., & Hackett, L. P. (2006). Effects of caffeine on prolonged intermittent-sprint ability in team-sport athletes. Med Sci.Sports Exerc., 38, 578-585.

- Silverman, K., Mumford, G. K., & Griffiths, R. R. (1994). Enhancing caffeine reinforcement by behavioral requirements following drug ingestion. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 114, 424-432.

- Smith, A., Thomas, M., Perry, K., & Whitney, H. (1997). Caffeine and the common cold. J Psychopharmacol., 11, 319-324.

- Spriet, L. L., MacLean, D. A., Dyck, D. J., Hultman, E., Cederblad, G., & Graham, T. E. (1992). Caffeine ingestion and muscle metabolism during prolonged exercise in humans. Am J Physiol, 262, E891-E898.

- Stuart, G. R., Hopkins, W. G., Cook, C., & Cairns, S. P. (2005). Multiple effects of caffeine on simulated high-intensity team-sport performance. Med Sci.Sports Exerc., 37, 1998-2005.

- Tremblay, A., Masson, E., Leduc, S., Houde, A., & Despr+®s, J. P. (1988). Caffeine reduces spontaneous energy intake in men but not in women. Nutrition Research, 8, 553-558.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Katherine Lim by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/ultrakml/6064602856/

Your thoughts on this