People like labels, boxes, neat categories.

People like to be able to place others somewhere, to have them all figured out.

Knowing how old someone is, where they grew up, where they went to college, what their religion is, what political party they vote for, and things like that, can represent a kind of social gel — an easy way to begin to assess where they stand in relation to us.

They can also make for some awkwardness. How is someone whose four biological grandparents all hailed from different countries, but they were born in a fifth place and then adopted by people from yet another ethnic group, only to grow up in a sixth place, supposed to answer that quintessential small-talk question, the one that seems to come up above all else and the only one that appears to be universally socially acceptable — "Where are you from?"

Categorizing people is a process often engaged in subconsciously, but it doesn't take much thinking to come to the conclusion that asking what turns out to be rather narrow-minded questions can easily contribute to another person's existential crisis.

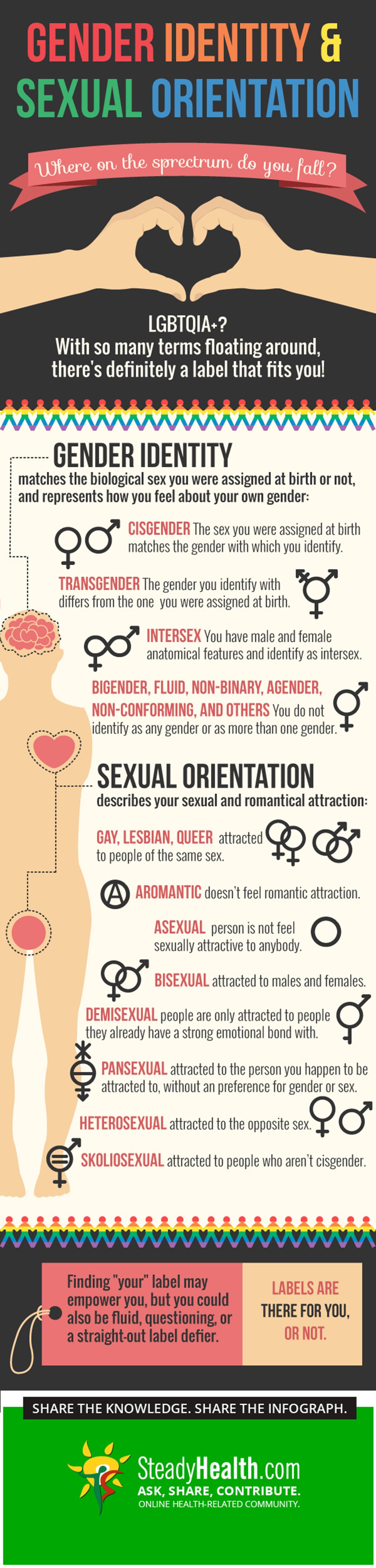

Have You Found Your Label Yet?

In a fascinating paper titled "The Magical Age of 10", two people named Gilbert Herdt PhD and Martha McClintock PhD wrote, in 2000: "Accumulating studies from the United States over the past decade suggest that the development of sexual attraction may commence in middle childhood and achieve individual subjective recognition sometime around the age of 10. As these studies have shown, first same-sex attraction for males and females typically occur at the mean age of 9.6 for boys and between the ages of 10 and 10.5 for girls."

Further research reveals that over 10 percent of males and females respectively begin self-identifying as gay or bisexual in grade school, with 48 percent of gay and bisexual students having figured out their sexual orientation during their high school years. "Finding your label", scientific consensus suggests, requires no sexual experience and generally happens on its own in adolescence.

What if you don't have it all figured out though? What if you aren't sure whether you are gay, bisexual, straight, none of the above, or something else? What if your sense of sexual identity was quite clear-cut, thanksverymuch, only for you to become romantically attracted to or fall in love with someone who diverged from your previous pattern of attractions so much that you are now questioning your sexual orientation? What if you do have a deep sense of falling into one particular category but deeply wished you could change, or are, on the contrary, pressured by those in your social circle to try to change? Could you?

The Kinsey Scale Of Sexual Orientation

Back in 1948, that is, quite a while back, a guy called Alfred Kinsey and some of his colleagues introduced the Kinsey Scale, with a rather revolutionary commentary for the time. "Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats. It is a fundamental of taxonomy that nature rarely deals with discrete categories," they wrote, adding: "An individual may be assigned a position on this scale, for each period in his life."

Holding that "a seven-point scale comes nearer to showing the many gradations that actually exist", they proposed one. It looks like this:

- 0: Exclusively homosexual

- 1: Predominantly heterosexual, only incidentally homosexual

- 2: Predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual

- 3: Equally homosexual and heterosexual

- 4: Predominantly homosexual, but more than incidentally heterosexual

- 5: Predominantly homosexual, only incidentally heterosexual

- 6: Exclusively heterosexual

- X: No socio-sexual contacts or relationships

The Kinsey Scale, which the Huffington Post quite accurately labeled "so 1948", has received a stream of criticism since it first came out. Among the things that must be mentioned if you are currently trying to figure out your own sexuality are these. The Kinsey Scale makes no distinction between internal sexual preference and sexual behavior. The Kinsey Scale does not acknowledge the presence of more than two genders. The Kinsey Scale's sliding tendency seems to suggest that the more you are attracted to one gender, the less you are attracted to another; something that isn't necessarily true at all.

READ Is Binary Transgender Acceptance Another Trap For Non-Binary Trans People?

What the Kinsey Scale did do, however, was acknowledge that sexual orientation might be a whole lot more fluid than our current world seems to want to be. It indicates that a person might fall somewhere on this scale at one point in their life, while ending up somewhere else at another point. This is a concept many people find difficult to grasp nowadays. There is a good reason for that — more about this on the next page. However, this more rigid interpretation of the nature of human sexuality won't be doing you any favors if you feel limited by it.

'Born This Way" And 'Gay Conversion Therapy'

This world counts numerous people who believe homosexuality to be a sin — a sin they do not only have the right, but even a duty to correct, in whatever ways they personally deem acceptable. Forget a US conservative Christian baker's refusal to make a "gay wedding cake": both in the past and in the present in various countries, being gay or perceived as such has (had) such implications as facing the death penalty, being denied access to children, being denied employment, being denied access to healthcare, and being subjected to utterly cruel treatments to "correct" the person's homosexuality.

In the modern western world, "gay conversion therapy" is one form discrimination against non-heterosexual people may take on. As Exodus International, one of the largest groups advocating this practice, says:

"We believe same-sex attractions are one of many ways that people experience fallen humanity. Christians and non-Christians can both experience same-sex attractions. For some people, same-sex attractions are unwanted attractions that bring struggle and confusion into their lives. Some people embrace these and become involved in homosexuality. People within the church who experience same-sex attractions may have difficulty finding support in the church or from family members. People outside the church often think that God and the church to be against them rather than offering hope, welcome and help. Yet the message of Scripture is that God’s love brings hope and help.

While anyone can experience same-sex attractions, engaging in homosexual behavior distorts God’s intent for people and is sinful."

OK. That was long, and as boring as it is horrifying. I'm sorry for subjecting my readers to that. It is important, however. Exodus International adds what they actually do when someone contacts them for "support": "Exodus will refer you to the Exodus Member Ministries that are close to you. Most of our Member Ministries are non-professional Christian ministries that provide some combination of Christian fellowship, discipleship, counseling and support group services." Yep, that's right, you've landed in the world of "pray the gay away", a practice that is all too common — and perhaps even something your parents want you to attend if you are a young queer person, or something you yourself may feel called to turn to, after a lifetime of being taught that homosexuality is a sin.

Does it work? Of course not. The consensus among mainstream psychologists is that this is a dangerous and ineffective practice, one that can make feelings of self-hatred and anxiety grow in those who are falsely being treated for something perfectly normal.

The defense against this kind of damaging nonsense? "We were born this way, and there's nothing you can do to change it." Indeed, studies suggest that genes themselves represent up to 30 percent of differences between people of different sexual orientations, and that genetic markers are indeed rather likely to explain part of the puzzle. Part of the puzzle isn't all of the puzzle, though. Hormones, too, are inherent. But then there are other factors, both social and as yet unexplained ones.

One thing is clear: inhumane "therapy" techniques aren't going to change my sexuality any more than they will change my age or ethnic group (though if I have no choice but to attend them, they may just change what I say about these things in public, and even, perhaps, the actions I take — nice world we live in).

However, while research is still emerging, people's lives carry on, and people sometimes find themselves genuinely self-identifying as straight at one point in their lives, gay at another, and pansexual at yet another, or those people may find themselves falling in love with a person because of who they are rather than what their gender is, or they may find themselves in a relationship with a trans person in transition. Then, there are those who never felt conventional labels applied to them in the first place.

READ Are You Ready To Lose Your Virginity?

As research on human sexuality continues to emerge, people's lives carry on, and there are indeed those who self-identify as one sexual orientation at one point in their lives, but another later down the road. We might simply not have the vocabulary to express the full range of human sexual experience yet.

- Infographic by SteadyHealth.com

- borngay.procon.org/view.answers.php?questionID=000014

- www.exodusglobalalliance.org/whatwebelievec86.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinsey_scale

- www.huffingtonpost.com/patrick-richardsfink/kinseys-scale-is-so-1948_b_2362996.html

- www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2015/jul/24/gay-genes-science-is-on-the-right-track-were-born-this-way-lets-deal-with-it