Around a fifth of people infected with the hepatitis C virus are lucky — their bodies clear the virus spontaneously, within the first six months after exposure, and without treatment. For the rest, the infection becomes chronic. Though treatment is now able to cure about 90 percent of cases, not everyone living with hepatitis C knows they're infected, and not everyone who knows they're infected has access to treatment. Different strains of hepatitis C exist, and even people who were treated for hepatitis C and cured can again contract either the same genotype or a different one; there's no life-long immunity for those who had the condition once.

What do you need to know about cirrhosis and hepatitis C?

What is hepatitis C, and how does it damage the liver?

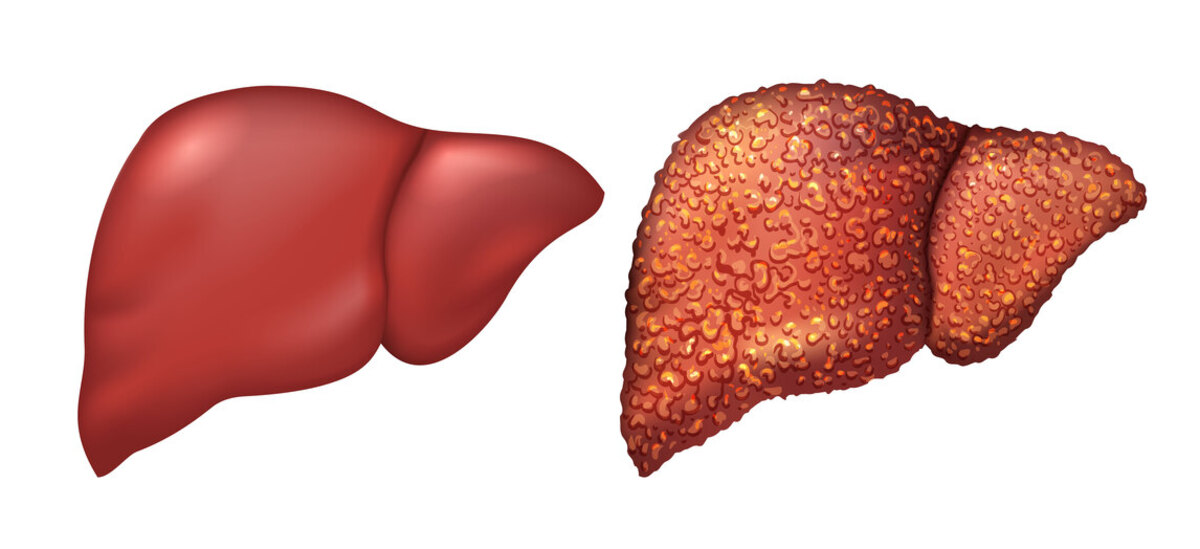

Hepatitis C is a viral disease of the liver. The fact that this small RNA virus is solely hepatotropic means that it only targets your liver — but it's pretty efficient at doing so, damaging and destroying liver cells after exposure. Over time, this can have severe consequences for people who develop a chronic infection, especially if they do not receive treatment. The many thousands of people who die from causes related to hepatitis C mainly succumb to primary liver cancer as well as cirrhosis.

Hepatitis C is spread through contact with infected blood, and is the most common chronic viral infection of this kind in the United States, where the most likely way to get the infection is through injecting drugs, and especially sharing needles and syringes. Other ways to get infected include receiving unregulated tattoo or piercing, sharing personal care items such as razors and toothbrushes with an infected person, being born to a mother who is positive for hepatitis C, and more rarely through unsafe sex (which can cause microlacerations and thus lead to exposure to blood). Receiving blood transfusions and organ transplants used to pose a risk, and it still might in countries where rigorous testing is lacking. Healthcare workers and correctional officers are especially at risk of needlestick injuries, which can also transmit hepatitis C.

Though chronic hepatitis C has the potential to cause serious and even fatal complications, the infection doesn't necessarily "announce itself" in a way that makes people think, "yes, I've definitely got some kind of viral hepatitis".

Hepatitis C is, as such, sneaky. To reduce the risk of complications, including cirrhosis, you need treatment. To access treatment, you need to know you have it. To know you have it, you must get tested. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control recommend that you get tested for hepatitis C if you:

- Were born between 1945 and 1965.

- Were the recipient of an organ donation or blood transfusion before 1992.

- Have ever used IV drugs — yes, even if it was just once, even if it was a long time ago and you haven't had symptoms, and even if you didn't share needles.

- (Think) you have been exposed to the blood of someone who (potentially) has hepatitis C.

- Have liver disease, HIV, or are on hemodialysis. Babies born to mothers with hepatitis C should always be tested as well.

What is cirrhosis?

Cirrhosis is a condition in which permanent liver damage leads to extensive scarring, which replaces normal liver tissue and obstructs blood flow. It isn't exclusive to people with chronic viral hepatitis, and you probably know that people who have abused alcohol for a long time are at risk.

In the United States, around one in 400 people are believed to live with cirrhosis. As with hepatitis C, they won't necessarily know they have it until much later on, when the damage becomes overwhelming and they develop symptoms. These can include feeling fatigued, vomiting blood, dark, blood-stained stool, itchy skin, easy bruising, edema (swelling of the lower limbs) and ascites (a fluid buildup in the abdomen, which you will recognize from pictures of starving children).

Cirrhosis itself can lead to complications, including:

- Portal hypertension, high blood pressure in the portal vein because scar tissue obstructs blood flow.

- Liver cancer.

- Liver failure.

- Vulnerability to bacterial infections.

What can you do if you have cirrhosis?

You can do your part to slow down the progression of cirrhosis by leading a healthy life. That means no alcohol, a healthy diet (as directed by your doctor), and maintaining a health body weight. It also means consulting your doctor before taking any over-the-counter medications (which may damage the liver further), and taking the drugs they prescribe you as directed. People with cirrhosis should also receive vaccinations, like flu shots and pneumonia shots, to reduce the risk of infections.

Ultimately, however, a liver transplant becomes the only option.

A final word

If, by any chance, you're reading this as a person who, as far as you know, doesn't have hepatitis C let alone cirrhosis, remember a few things.

A significant portion of us will have done at least one of those things in our lives, and that means there's a potential risk. If you recognize that potential risk in yourself, get tested. Should the outcome not be what you were hoping for, you can take comfort in knowing that the risk of serious complications is reduced when you receive treatment, and hepatitis C can even be cured.

- Photo courtesy of SteadyHealth

- www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/PDFs/HepCGeneralFactSheet.pdf

- www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1

- www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c

- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/viral-hepatitis/hepatitis-c?dkrd=hispw0192

- www.nhs.uk/conditions/cirrhosis/

- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/cirrhosis/definition-facts

- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/cirrhosis/treatment

Your thoughts on this