Dieting — be it for health reasons or aesthetic reasons — has become a hot topic of discussion in modern societies. Studies, discussions and controversies follow one another and, in the mind of the lay community many doubts and misunderstandings persist. In fact, one could argue that misinformation is the main reason dieting raises so many questions. In the following paragraphs, we’ll try to break down the benefits and disadvantages of some of the most popular forms of dieting with the help of reliable scientific data.

If a person is on a diet, they’ll typically favor the ingestion of particular types of foods and beverages over others and, more often than not, this is paired with some form of physical exercise – especially if the aim is to lose weight.

Unsurprisingly, it’s weight loss diets that get the most attention. In fact, in light of escalating rates of obesity and its related co-morbidities, there has been an unprecedented quest for effective and safe weight-loss strategies by health-care practitioners, industry and the public. The most common weight loss diets can be divided in four large groups: low-fat diets, low-carbohydrate diets, low-calorie diets, and very low-calorie diets. Here we will consider the benefits and disadvantages of calories-restricting diets.

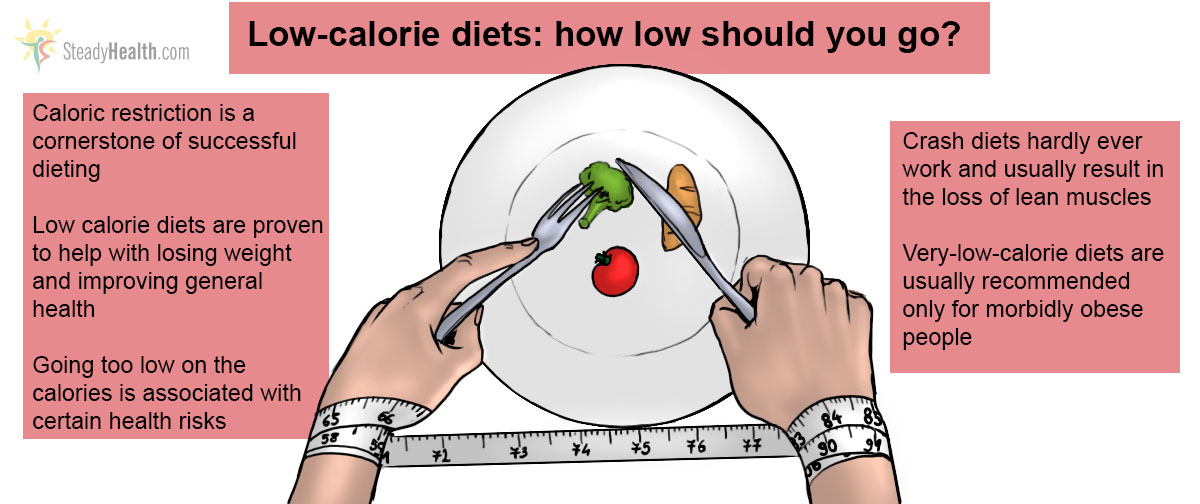

Low-Calorie Diets: How Low Should You go?

Low-calorie diets are those in which an individual reduces the daily caloric intake to an amount that is inferior to his or her previous intake or inferior to the average caloric intake of a person of their age. This practice, commonly known as caloric restriction, has gained widespread recognition in recent years, as research in several animal species has shown that caloric restriction without malnutrition increases one’s lifespan and improves their overall health state.

Traditional approaches to the weight loss have actually been based on the prescription of diets that provide an energy intake below that of an energy expenditure, i.e., an energy (or in common parlance calorie) deficit. Reducing the energy content of a diet can be achieved by reducing the intake of protein, carbohydrate, or fat alone or in combination. At the same time one or more macro-nutrients can be increased (within an overall energy restriction). Frequently, though, low-calorie diets encompass a balanced proportion of protein, carbohydrate, and fat in reduced amounts to provide an energy intake of 800 to 1500 kcal per day.

When done adequately, calorie restriction is the cornerstone of obesity therapy. It induces weight loss, therefore improving multiple metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease and other medical abnormalities associated with obesity. Therefore, even if calorie restriction does not prolong maximum life span, it could increase life expectancy and the quality of late life by reducing the burden of chronic disease.

See Also: Should You Count Calories?

Going Too Low On Calories May Be Harmful

Restricting the consumption of calories must be done with great care, so as to avoid situations of malnutrition. The “Minnesota Starvation Experiment,” performed between 1944 and 1945, constitutes the very first systematic evaluation of the outcome of strict calorie restriction in individuals with normal weight. In this study, baseline calorie intake was reduced by 45% for 24 weeks in lean men. On one hand, these men exhibited the positive effects of calorie restriction, such as a decrease in body fat, blood pressure, improved lipid profile, low serum triglyceride concentration, decreased resting heart rate and lowered whole-body resting energy expenditure. On the other hand, this considerable calorie restriction also had severe harmful consequences, including anemia, muscle wasting, neurological deficits, lower extremity edema, weakness, dizziness, lethargy, irritability, and depression.

Extreme Calorie Restriction Is Not For Everyone

The negative effects become even more pronounced with more significant caloric restrictions. The majority of popular crash diets result in some weight loss caused by the loss of lean muscles rather than the fat. In fact, upon completion of crash diet programs many people have even higher percentage of body fat than before the diet.

Very Low-Calorie Diets

Very low-calorie diets, as the name suggests, are characterized by the consumption of a much reduced amount of daily calories (800 kcal or less). These diets involve ingesting specific, highly regulated, commercial preparations that are nutritionally complete. This means that despite their low calorie count, these liquid meals include the recommended daily quantities of vitamins, minerals, trace elements, fatty acids and protein. Depending on a particular approach, the carbohydrates may or may not be entirely absent.

Understandably, and unlike any usual calorie restriction diets, very low-calorie diets are actually a part of a complex dieting program that also includes close medical monitoring and lifestyle modification. Each person must be closely supervised by a physician, to avoid metabolic issues, namely negative nitrogen balance and electrolyte changes associated with starvation. Furthermore, very-low-calorie diets are restricted to people with a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2, with a very high risk of several diseases, and for whom other approaches have failed. In the United States, all candidates for the very-low-calorie dieting are expected to undergo a medical history and physical examination to determine possible medical and behavioral contraindications to this treatment.

The effectiveness of very-low-calorie diets in kick-starting the reduction in one’s body weight is unquestionable. Very-low-calorie diets result in an average weekly weight loss of 1.5–2.5 kg. However, it has been observed that, in the long term, this elevated rate of weight loss is not maintained. Very-low-calorie diets should not be extended beyond 16 weeks. At this point, low-calorie diets should be initiated in order for the patient to transition to a normal eating pattern.

Very-low-calorie diets are associated with a variety of side effects and with numerous complications, such as cholelithiasis (formation of gallstones in the bladder), loss of lean body mass, ketosis and increased serum uric acid concentrations due to the severely negative energy balance.

Overall, very-low-calorie diets present a number of medical risks but offer rapid weight loss. Intensive monitoring is required on the part of the physician, and patients must learn to maintain their weight loss when returning to normal eating patterns.

Although science cannot provide a definite answer on which diet is the best, it is clear that restriction of calories intake (and proper adherence to the diet regime) is the key to the successful weight loss.

See Also: Diet Tips To Help Lower Calorie Intake

All of the most popular types of diet have benefits and disadvantages and it is up to each and every one of us to make informed and conscious decisions about the practices that will impact our bodies’ welfare. The next article will discuss the benefits and disadvantages of some of the most popular types of diets, such as those based on restriction of certain nutrients like fats or carbohydrates.

- TSAI, A. G. & WADDEN, T. A. 2006. The Evolution of Very-Low-Calorie Diets: An Update and Meta-analysis. Obesity, 14, 1283–1293

- SARIS, W. H. M. 2001. Very-Low-Calorie Diets and Sustained Weight Loss. Obesity, 9, 295S–301S

- MALIK, V. S. & HU, F. B. 2007. Popular weight-loss diets: from evidence to practice. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 4, 34-41

- FONTANA, L. & KLEIN, S. 2007. Aging, Adiposity, and Calorie Restriction JAMA, 297, 986-94

- VOLEK, J. S. & WESTMAN, E. C. 2002. Very-low-carbohydrate weight-loss diets revisited. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 69, 849, 853, 856-8

- HOOPER, L., ABDELHAMID, A. & MOORE, H. J. 2012. Effect of reducing total fat intake on body weight: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ, 345, e7666

- LICHTENSTEIN, A. H. & HORN, L. V. 1998. Very Low Fat Diets. Circulation, 98, 935-939.Photo courtesy of Alan Cleaver by Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/alancleaver/4222532649

- Photo courtesy of Rachel Zack via Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/rachelmargaret/2885800615

- Mind map by SteadyHealth.com

Your thoughts on this