A note about the term 'Wegener's granulomatosis'

Wegener's granulomatosis (WG) is an outdated term for a condition now known as granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA). A new name was selected for the condition in 2011 for several reasons:

- Though the doctor Wegener the condition was named after in English was one of the earlier ones to describe the condition, he was not the first — and scientists have learned a lot more about the condition since it was first reported in the scientific literature. The new name reflects a greater understanding of the condition.

- The Dr Wegener after which Granulomatosis with Polyangitis was initially named was involved with the Nazi regime, something that further prompted modern scientists to change the name of the condition.

What is Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis?

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA) is not a contagious disease as many people believe. There is no evidence suggesting that it is hereditary, either. About 500 new cases are diagnosed each year, among people of all ages. However, it mostly affects individuals in their 30s and 40s. Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis affects males and females equally, but 97 percent of all patients are Caucasian, two percent are Black, and one percent are of another race. With Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, it is extremely important to know more about diagnosis and its treatment.

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is a rare disorder that causes blood vessels in the upper respiratory tract (nose, sinuses, and ears), followed the by lungs and kidneys, to become swollen and inflamed. The eyes, skin, and joints may also be affected, with arthritis occurring in about half of all cases.

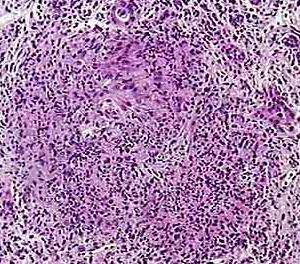

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is thought to be an autoimmune disorder. This uncommon disease usually begins as a localized granulomatous inflammation of the upper or lower respiratory tract mucosa, and may progress into generalized necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis and glomerulonephritis. The cause of Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is unknown. Although the disease resembles an infectious process, no causative agent has been isolated yet. Because of the characteristic histological changes, hypersensitivity has been postulated as the basis of the disease.

Symptoms of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Frequent sinusitis is the most common symptom for Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Other early symptoms include persistent fever without an obvious cause, night sweats, fatigue, and malaise (an “ill feeling”). Chronic ear infections may preclude a diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

Other upper respiratory symptoms include nosebleeds, pain, and sores around the opening of the patient’s nose. Loss of appetite and weight loss are common as well. Skin lesions typically occur, but there is no one lesion associated with this disease. Symptoms of kidney disease may be present, but this does not always happen. The urine may be bloody, and usually it first appears as red or smoky urine. Eye problems develop in a significant number of patients, which may range from mild conjunctivitis to severe swelling of the eye. Other symptoms include weakness, cough, or coughing up blood, as well as bloody sputum. The patient commonly complains about shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain, rashes, and joint pains.

Diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis is diagnosed by examining characteristic clinical, serologic, and pathologic findings. GPA must be diagnosed and treated early to prevent complications. Common complications include kidney disease, lung disease, heart attacks, and brain damage.

A doctor can usually recognize the distinctive pattern of symptoms, although blood test results cannot specifically identify Granulomatosis with polyangiitis. However, these blood tests can strongly support the diagnosis. A blood test can detect antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in the blood, which suggest this disease.

If the nose, throat, or skin is not affected, a diagnosis can be difficult. This is because the symptoms and x-rays can resemble those of several lung diseases. A chest x-ray may show cavities or dense areas in the lungs similar to cancer. To definitely diagnose Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis, a variety of tests may be performed, including a biopsy of abnormal tissue. The doctor could choose to perform an open lung biopsy, upper airway biopsy, nasal mucosal biopsy, bronchoscopy with transtracheal biopsy, or kidney biopsy. Urinalysis is helpful to look for signs of kidney disease such as protein and blood in the urine. In fact, the presence of kidney disease is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

Treatment of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

Corticosteroids may be used alone to treat the early symptoms. However, most people also need another immunosuppressive drug, such as cyclophosphamide, to manage Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Imuran is a common choice. This drug is able to control the disease by reducing the body’s immune reaction, which improves the prognosis significantly. Without treatment, this form of the disorder is fatal. Treatment is usually continued for at least a year after the symptoms for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis disappear.

Corticosteroids, given at the same time to suppress inflammation, can usually be tapered off and discontinued during other treatment still last. For people receiving immunosuppressive drugs, a doctor treats any suspected infection as early as possible. This is because of the body’s decreased ability to fight infections during this therapy. Pneumonia is particularly common when the lungs are affected by GAP. Moreover, antibiotics may be used to prevent infections in people who have been taking immunosuppressive drugs for years. Treatment with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or azathioprine produces a long-term remission in over 90 percent of patients afflicted with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

With treatment, most people recover within months, although some may develop chronic renal failure. Without treatment, patients can die within a few months, which is why complications usually result from lack of treatment. Possible complications include chronic kidney failure, hemoptysis (coughing up blood), respiratory failure, or inflammation of the eyes. Common complications are also nasal septum perforation and rash. Moreover, medications used to treat the disease can cause side effects. These side effects may also lead to complications.

It is important to know when to call the health care provider. Anyone who experiences chest pain, coughing up blood, blood in the urine, or other symptoms of this disorder should call their health care provider. The problem is that no preventive measures are currently known.

Prognosis of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

With proper treatment, most people diagnosed with Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis recover within months. However, some may develop chronic renal failure. The complete syndrome usually progresses rapidly to renal failure once the diffuse vascular phase begins.

Patients with limited disease may have nasal and pulmonary lesions, with little or no systemic involvement, where pulmonary manifestations may improve or worsen spontaneously. A previously fatal prognosis can be been dramatically improved with the help of treatment with immunosuppressive cytotoxic drugs. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial, because a high remission rate is now possible. In fact, critical renal complications can be avoided or reduced. Cyclophosphamide, 1 to 2 mg/kg/day with oral hydration, or by initial rapid IV infusion as a single dose for two to three weeks is the drug of choice for Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

Corticosteroids, which reduce vasculitic edema, are given concurrently. It could be prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. After two to three months, prednisone is tapered until the patient is maintained solely on cyclophosphamide. This means long-term IV dosing appears to be less efficacious.

Azathioprine is less effective. However, this drug may be an alternative or adjunct to cyclophosphamide for patients who cannot tolerate cyclophosphamide. Pulse treatment with methotrexate seems to be a better alternative. Long-term prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole seems to be highly effective for upper respiratory tract lesions and may suffice as the sole long-term treatment once all systemic features have been ablated by cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids. Occasionally, the associated anemia may be so profound that blood transfusions are required due to this therapy.

Long-term complete remission can be achieved with proper therapy, even in the case of advanced disease. Kidney transplantation has been successful in renal failure, although a report of one patient who received a cadaver kidney implant showed that typical renal lesions of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis developed at the end. An increased incidence of solid tumors after many years may reflect high-dose cyclophosphamide use as a therapy of choice. The high incidence of bladder cancer many years after treatment is an alarming consequence of the hemorrhagic cystitis associated with excreted cyclophosphamide breakdown products. It is often unmitigated by high fluid output during initial therapy. Kidney lesions cause glomerulonephritis, which may result in blood in the urine and kidney failure at the end as serious consequences of Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis.

Read More: Lung Diseases: Emphysema & tobacco smoke

Kidney disease can quickly worsen, and if left untreated, kidney failure and death occur in more than 90 percent of patients.