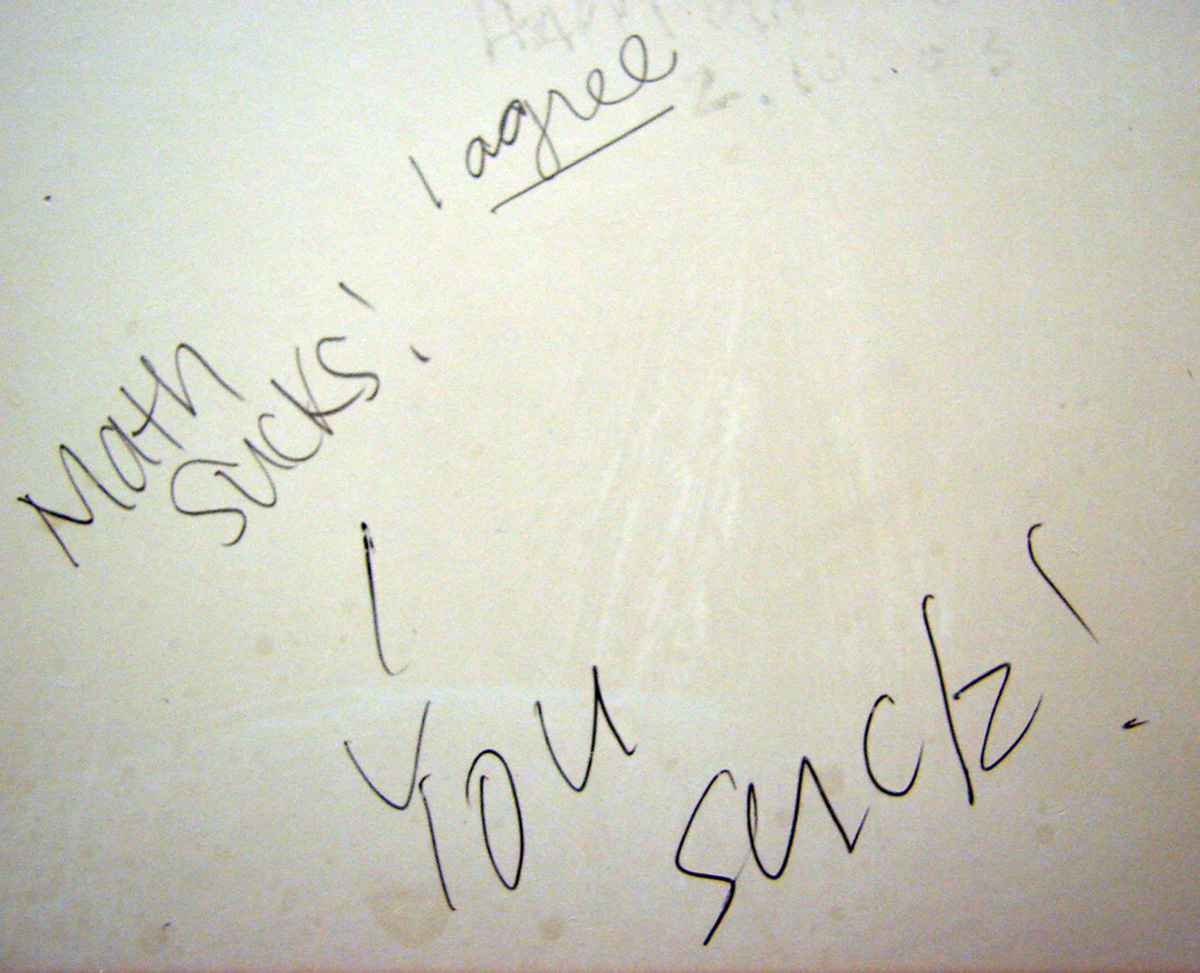

As my peers were learning to add and subtract, the weird symbols on the pages of my math textbook simply didn't make sense to me. Later on, as they mastered long division and multiplication, I had trouble playing board games because I couldn't add up the numbers on the dice, or even tell what the dots actually represented. Frustrated teachers told my mother I was lazy and defiant and she, in turn, tried to remedy my lack of understanding with more pages of stuff that didn't make sense.

By the time we were in high school, my peers were tackling other things I didn't understand — algebra, geometry, and calculus, I think these things are called. I still couldn't handle basic addition and subtraction, read music, or even tell the time on an analog clock. Math was such a problem for me that I nearly didn't graduate high school because of it. Even after I had kids of my own and was a competent, productive member of society, I had little idea whether cashiers gave me the right change.

"What is dyscalculia?" you may wonder if you have a child who simply doesn't seem to "get" math — no matter how many times you or anyone else tries to explain what is so obvious to most adults, and what comes quite naturally to most kids with little to no instruction.

Well, that, to me, is what dyscalculia is. Dyscalculia is when math is your nemesis; a scary, alien stranger everyone desperately wants you to get on with. If you are the parent of a kid who doesn't seem to understand math, this is a diagnosis you may be exploring.

What Is Dyscalculia?

Dyscalculia is a learning difference that significantly hampers a person's ability to do math, or at least arithmetic. The exact way in which math is troubling varies from dyscalculic to dyscalulic. Research into dyscalculia is still limited, no central data bank exists, and not everyone working with dyscalculia sufferers agrees on the exact nature of the learning difficulty. You may think of dyscalculia as dyslexia's less popular, less understood cousin.

Tony Attwood, founder of the British "Dsycalculia Centre", used online dyscalculia surveys to learn more about the disorder. This enabled him to come up with five distinct types of dyscalculia. Though there is still much to be learned about the disorder, Attwood's types can be very useful at helping others understand the various ways in which sufferers may be affected.

Type 1 dyscalculics, Attwood says, report significant worries about their mathematical abilities and cannot complete math-related tasks 90 percent of their peers have no problems with. Not only do they have serious trouble learning to understand math, they also lack helpful support from teachers and parents. They've developed a strong fear of math that convinces them that they cannot improve their abilities. Some may have developed a basic understanding of the four operations but can't get into more complex concepts, while others lack even those basics.

Type 2 dyscalculics are very similar in that they experience strong worries about their abilities, but they have learned some coping strategies. They may not be able to earn a passing grade on their high school math exams, but they can generally get by in day-to-day situations. The calculations they perform still take them much longer than they would take others.

Type 3 is characterized by a profound difficulty in understanding and coping with the concept of time and time passage. According to Attwood, this type of dyscalculic has problems with long- or short-term memory as well, and cannot handle tasks that require sequencing. This type is much rarer than the other types, and also more debilitating.

See Also: Dyslexic Child: How to Deal with Learning Problems

Type 4 may not be actually be dyscalculia at all, but memory and processing difficulties that manifest as an inability to do math. Not being able to remember sequences of numbers may make these people unable to compute anything. According to Attwood, they may also lack the support that might help them move beyond their difficulties, and they aren't typically diagnosed with memory issues.

Type 5 dyscalculics have trouble understanding how math relates to the real world. The abstract nature of math phases them to the point that they cannot come up with correct answers, or can get to correct answers without understanding what they actually mean.

Dyscalculia: What Now?

Signs And Symptoms

Children with dyscalculia have difficulty learning to count, do basic arithmetic, remember numbers, or apply learned knowledge to real-life situations. Patterns are also likely to cause difficulty. It's important for parents and teachers to understand that these difficulties arise from a learning difference and not laziness or defiance, something many older dyscalculics were "accused of". Learning to understand mathematical concepts that come naturally to most other children seems impossible for dyscalculics, and more practice or remediation does not solve the problems.

Why Does Dyscalculia Develop?

Studies indicate that dyscalculia has a genetic component. Several of my relatives also have difficulties with math, and others have been diagnosed with dyslexia, so I have seen this in action. As dyscalculia is taken more seriously, more research is conducted. Brain imaging has shown that dyscalculics have physical brain differences that could explain why math doesn't make sense to them. These brain areas are related to memory, learning, and fact recollection. Prematurity, alcohol exposure in utero, and even brain injury later in life can also lead to dyscalculia, research suggests.

Now, What Can You Do About It?

Back in my day, parental support and the support of other relatives was extremely useful. This support mostly came in the form of an acknowledgement that I honestly, truly could not understand math concepts, despite trying very hard for many years. The day someone told me that forcing me to do math would be a bit like forcing a wheelchair user to run was liberating. I accepted my learning difference and learned to get by with calculators.

Things have moved on since that time, though, and some dyscalculics do overcome their math difficulties with the right approach and curriculum (look up Ronit Bird!). The ability to overcome dyscalculia starts with the correct diagnosis, though. Diagnostic criteria vary from country to country, but you'll always be looking at testing with healthcare professionals like developmental psychologists, or in some cases pediatricians. Your child's public school may make evaluations available, or you may need to look into getting your child evaluated privately.

You don't want your child to take remedial classes from math teachers who are not familiar with the condition — a new approach is needed if your child is ever to move beyond their current abilities, or lack thereof. You may also investigate curricula that make more sense to your child privately, and use math manipulatives such as cuisenaire rods to demonstrate what the numbers your child is trying to work with actually mean.

I have personally had luck with the Singapore approach to math, specifically the curriculum "Primary Mathematics", published by Marshall Cavendish. Though this curriculum has a reputation as one that works best with "mathy" kids, it does explain concepts in a manner traditional western math curricula do not. The home instructor's guides are very helpful in helping parents and teachers explain concepts. Thanks to this curriculum, I am now able to do math at a fourth grade level. (Did I mention I am nearly 40 and a mother of two? I am immensely proud of my new abilities though!)

There's something to be said for focusing on developing your child's natural strengths instead of banging your head against a wall. Many dyscalculics will never be able do well in careers that require math, and looking for career options that suit your child better may be more productive than pouring your energy into making your child do something that will simply never happen.

Should math be a graduation requirement, your situation is a little (a lot?) more difficult. Your best bet lies with finding experts who really understand dyscalculia (offline and online), and focusing on getting to the point where a passing grade is attainable. You may be able to play a role as a powerful and loyal advocate for your child. If the school is willing to make accommodations, try to get the most out of that. While some dyscalculics may benefit from having more time to complete tests, others won't find that at all useful. Just staring at something you don't understand for longer won't make much of a difference, will it? Allowing dyscalculics who are unable to do mental arithmetic the use of a calculator is a much more universally beneficial move. Some will be able to grasp and engage in higher math concepts, as long as they can do the basic calculations on a calculator.

See Also: The Influence Of Genes On Reading And Mathematical Abilities

One final suggestion. If you do live in a country where math is a graduation requirement, you may want to look into having your child take British IGCSE exams instead of sitting for local high school exams. British qualifications are offered on a subject-by-subject basis. For some dyscaculics, this could be the difference between being able to attend university and being stuck without as much as a high school diploma.

- Photo courtesy of quinn.anya via Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/quinnanya/3591929315

- Photo courtesy of Woodleywonderworks via Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/wwworks/8068812979