The headlines sound as if they were ripped from the Middle Ages, if the Middle Ages had had newspapers with headlines, that is. A fresh outbreak of bubonic plague, the Black Death, was reported in Madagascar last month. 84 cases were diagnosed, with the majority of those determined to be the more virulent form of the disease. Almost half of those infected died. The plague is not limited to less-developed areas, either.

The last epidemic in the USA was less than one hundred years ago. The Black Death certainly has staying power.

Where Does the Plague Come From?

Bubonic plague comes to us courtesy of a little bacteria named Yersinia pestis. As you may remember from your history lessons, this bacteria lives out its life cycle within the fleas that infest rodent populations throughout the world. Rats, squirrels, prairie dogs, mice, rabbits, even armadillos, all are host to fleas that carry the plague bacteria. The fleas, rodents, and bacteria have an enzootic relationship. The host animals have a steady infection rate without having an outbreak of the disease themselves.

The problem occurs when an epizootic cycle occurs. This is when the infection leaps to a different species and actually makes that species sick. This can happen either by other animals eating dead rodents that were plague hosts or by Yersinia pestis-carrying fleas biting other animals and transmitting the bacteria directly. Cats that contract the plague become very ill and can spread the disease to humans by coughing and sneezing. Dogs rarely become ill themselves, but they carry the infected fleas into homes.

What Does the Plague Do?

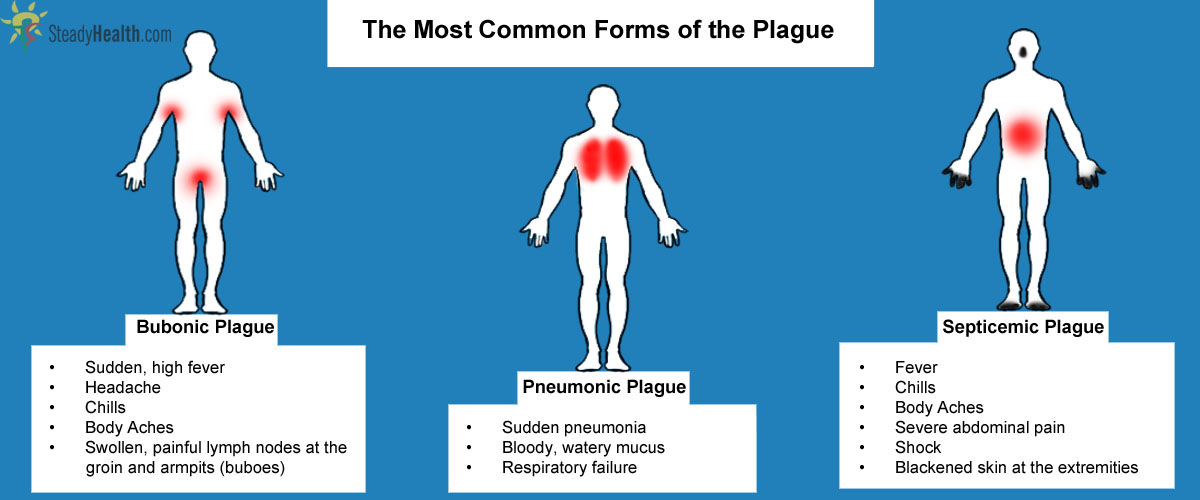

The symptoms depend on the form of plague. There quite a few kinds, but the most common ones diagnosed are bubonic plague, septicemic plague, and pneumonic plague.

Bubonic Plague

People usually contract bubonic plague through the bites of infected fleas. There is a sudden, high fever along with headaches, chills, and body aches. It could be confused with a bad cold or the flu, but for the buboes. These are swollen, infected lymph nodes that develop under the arms and at the groin. They are very enlarged and extremely tender and painful.

Septicemic Plague

Septicemic plague is what people are referring to when they call the plague "Black Death." It is also spread by flea bites, but can be contracted by handling dead animals that were infected. Septicemic plague can present as the first sign of infection or it can develop from untreated bubonic plague. Along with the fever, chills, and body aches of bubonic plague, septicemic plague also causes severe abdominal pain and shock. The disease microorganisms spread through the blood and those infected actually begin bleeding into their skin and organs. The skin turns black and dies.

Read More: Once An Almost-Forgotten Disease, Measles Outbreak Strikes Children And Adults

Pneumonic Plague

Pneumonic plague is the most serious form, both for its virulence and its ease of transmission. It's contracted by inhaling droplets from other infected people or by leaving bubonic or septicemic plague untreated. There is a sudden onset of pneumonia that is accompanied by watery, bloody mucus and can lead to respiratory failure. This is the only form of plague that is spread directly from person to person.

Should We Bring Out Our Dead?

No, don't bring out your dead.

In modern times, the plague remains a serious illness, but it is easily treated... if it is diagnosed early.

When Should I Suspect the Plague?

In the United States, the vast majority of plague cases occur in the western region with the bulk of cases diagnosed in northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, and southern Colorado. People who live in those areas or who have recently traveled there should be tested for plague if they present with the typical symptoms, especially swollen lymph nodes or buboes, and if they have known flea bites.

You should suspect the plague, a bacterial infection caused by Yersinia pestis, if you experience sudden onset of fever. The fever may develop rapidly and be accompanied by chills and severe body aches. Also, if you have painful swollen lymph nodes. One of the hallmark symptoms of the plague is the development of swollen lymph nodes, known as buboes. Buboes are often located in the groin, armpit, or neck region. They are usually tender, warm to the touch, and can increase in size rapidly.

The initial symptoms of the plague can resemble those of the flu, including headache, fatigue, muscle aches, and general malaise. These flu-like symptoms may precede the characteristic manifestations of the plague.

n some cases of the plague, particularly the pneumonic form, respiratory symptoms may be present. These can include coughing, chest pain, and shortness of breath. Pneumonic plague is a severe and rapidly progressing form of the infection that primarily affects the lungs and can be transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets. In rare cases, the plague can present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

How is the Plague Treated?

If doctors suspect plague, antibiotics are started even before results come back from laboratory testing. Both adults and children begin a course of strong antibiotics, either injected directly or administered intravenously. Streptomycin and gentamicin are the antibiotics of choice, although alternatives are available if needed. The antibiotic regimen is administered for at least 10 days or until the patient has been fever-free for two days.

Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is recommended for people who have had known exposure to the plague, either through close contact with a person diagnosed with pneumonic plague or from handling diseased tissues. In those cases, a course of oral doxycycline or ciprofloxacin is administered in order to prevent infection.

Supportive care plays a crucial role in the management of severe cases of the plague. The aim of supportive care is to provide comfort, manage complications, and help the patient's body fight the infection.

Supportive care is typically provided in a hospital setting, where healthcare professionals can closely monitor the patient's condition and address any emerging needs. The specific interventions and level of care required may vary depending on the severity of the infection and the individual patient's response to treatment.

How Can I Reduce My Risk?

The best way to reduce your risk of contracting the plague is to eliminate rodent populations around your home and outdoor spaces. Keep your yard free of brush, stack firewood neatly, and store animal feed in rodent-proof containers.

Wear gloves if you need to dispose of one, but if the corpse is crawling with fleas, give your local health department a call and have them handle it or at least give you some advice.

If you enjoy hiking and camping, use a quality flea repellent on your skin and clothes before venturing out. Domestic animals, such as cats and dogs, should also be supplied with quality flea repellents as it's more likely that they will get into areas that are flea-infested. Even with this protection, animals that are allowed to roam outdoors should not be brought inside the house if you live in a plague-endemic part of the country.

Read More: Leprosy - Unfinished Story

Be aware of any local outbreaks or areas with reported cases of the plague. Stay updated on public health advisories and follow any recommendations or guidelines provided by health authorities.

Fifteen diagnosed cases per year means the overwhelming majority of people in the United States will never experience the plague in any way, shape, or form. However, news reports like the one out of Madagascar remind us that the plague still remains a virulent and deadly foe for many around the world.

- Plague. (2001). In Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary (pp.1597-1598, Edition 19). Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Jesse Flanagan by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/tetrad/6305368344/