In the early part of the twentieth century, the bacterial infection known as whooping cough, caused by the diphtheria bacterium, Corynebacterium diphtheria, was the dreaded killer of young children and older adults all over the world. In the United States alone, up to 200,000 children per year caught the infection and as many as 15,000 died.

In Europe, in 1943 alone, over 1,000,000 people caught the disease and at least 50,000 died. And as recently as 1994 in Russia and 2010 in Haiti, diphtheria infections spread to thousands of people causing hundreds of death.

In the United States, diphtheria infections continue to crop up among recent immigrants and travelers, among homeless people, in prisons, and among the poor. The disease has been almost unknown among people who get diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus vaccinations (DPT shots), but scientists now believe that the vaccinations may not be completely effective against a new strain of the bacteria that cause the disease.

What's So Bad About Diphtheria?

Diphtheria is bacterial infection of the upper respiratory tract. Most commonly spread during the late winter and early spring, these bacteria cause symptoms beginning with a mild sore throat, flaring nostrils, and sinus pain.There can be a fever of up to 103 F (about 39 C), hoarseness, laryngitis, loss of appetite, fatigue, and difficulty swallowing.

But as the infection progresses, dead bacteria, dead white blood cells, dead red blood cells, and dead mucous membrane cells can accumulate into a thick, gray film that can settle just about anywhere in the nose, throat, or lungs. When this membrane forms, the resulting cough is diagnosed as pertussis, which is just the disease caused by a diphtheria infection.

It is this gray film that causes the most deadly symptoms of diphtheria. This so-called pseudomembrane can block the passage of air through the nostrils, the throat, or the lungs. It becomes a struggle to breath, with each cough causing an unmistakable "whoop" that is the hallmark of the disease. The infection can also cause extreme swelling in the neck that likewise interferes with breathing. If pieces of the pseudomembrane break off and are aspirated into the lungs, or if they block the breathing passages completely, respiratory failure and death may quickly follow.

How Is Diphtheria Treated?

The mainstay of diphtheria treatment is the administration of an antitoxin. This is not a vaccine. It is a treatment that keeps the toxin released by the diphtheria bacteria from killing tissues that slough off into the sticky pseudomembrane. Since the antitoxin is made from blood plasma from horses, people who are allergic to horse dander may not be able to take it.

Then the infection is treated with antibiotics. Infants can't be given erythromycin, because it can cause a narrowing of the digestive tract. The alternative to erythromycin is penicillin, but people also can be allergic to penicillin, greatly limiting the possibilities for effective treatment after the first few days of the disease. The infection can spread to joints, muscles, and the central nervous system, sometimes causing septic shock, blindness, total paralysis, and death in people who survive the whooping cough and respiratory obstruction induced by the disease. Even today, diphtheria can be fatal.

What Is the Problem With Diphtheria Vaccinations?

In 2012, public health officials in the United States and Australia were baffled that unusually large numbers of children were coming down with pertussis. At first, this result simply did not make any sense. The diphtheria vaccine was actually stronger than it had been in 1990's and early 2000's, when the rates of infection were much lower. There was no obvious reason that more children, and adults, were coming down with the disease.

Epidemiologists in Australia and the USA came up with several explanations of the increased rate of infection:

- Some parents did not want their children to get vaccinations. These children caught the infection and spread it to others.

- The new vaccine might have been "too strong" and weakened the immune system so that it provided protection at first but the protection wore off in just a few years. Or,

- The new, stronger vaccine simply did not last as long as the older, weaker vaccine.

It turned out that the problem was that the new formulation of diphtheria vaccine simply wore off faster than the older vaccines. But by the time this problem was discovered, there was a new problem.

These newly evolved strains of bacteria have fewer competitors, that is, they don't have to compete with as many other bacteria for food and oxygen, so they are especially likely to cause infection.

The strain that is currently causing problems in the US and Australia seems to have originated in France and Finland, and spread to other countries by people who did not get any vaccinations at all. The French strain of pertussis bacteria has become so potent that scientists are investigating whether it really should be considered a new, separate organism called Bordetella pertussis, but this new microorganism still responds to the old vaccine.

Right now, the epidemiologists' answer to this problem is booster shots.

And why should you care?

The primary concern of public health officials is stopping the infection in older children, teens, and adults, who get very sick but usually survive, so they don't spread it to babies. Before the age of six weeks, babies cannot be given diphtheria vaccine. They are the most vulnerable to the disease. Most of the deaths from diphtheria in the United States, especially in the state of Washington, have occurred in this age group.

Or if you choose not to get immunized against diphtheria, pertussis, and whooping cough, at least be very careful to wash hands and avoid open coughs when you are around newborns.

- Aaby P, Benn C, Nielsen J, Lisse IM, Rodrigues A, Ravn H. Testing the hypothesis that diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine has negative non-specific and sex-differential effects on child survival in high-mortality countries. BMJ Open. 2012 May 22

- 2(3). pii: e000707. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000707. Print 2012.

- Valérie Caro, Annika Elomaa, Delphine Brun, Jussi Mertsola, Qiushui He, Nicole Guiso. Bordetella pertussis, Finland and France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 June

- 12(6). 987–989. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051283.

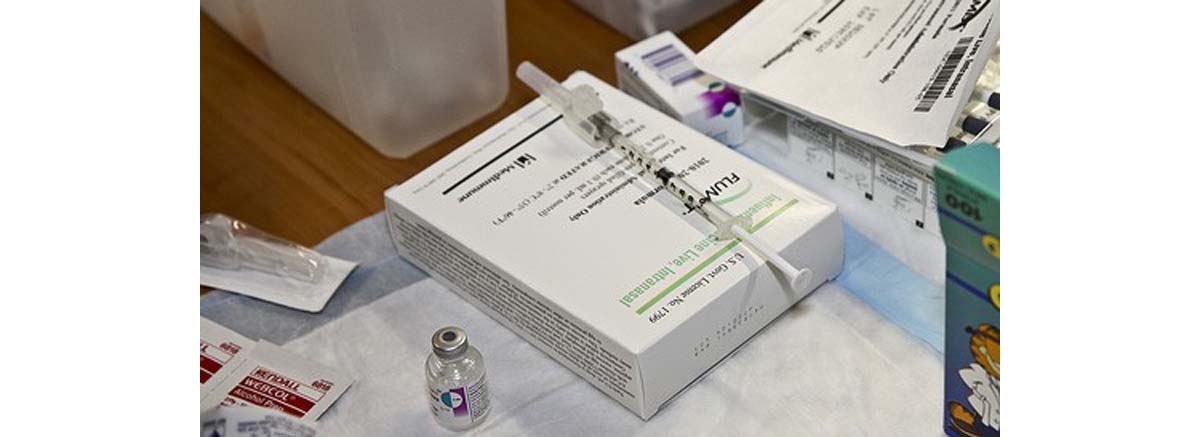

- Photo courtesy of europedistrict on Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/europedistrict/5181669792

- Photo courtesy of 51868421@N04 on Flickr: www.flickr.com/photos/51868421@N04/5277695536

Your thoughts on this