Table of Contents

Sprints are a great exercise for all kinds of outcomes and everyone should be doing them, but one thing they're great for is building speed and quickness - explosive, reactive speed-strength. Whether you're faking left and going right in basketball or catching someone out in cricket, those qualities give a winning edge. If you're not a sports person, you just use the gym to keep in shape, sprints still have a place in your training program. You'll find that programming sprints in boosts your overall athletic performance and improves speed, strength and power, making all your time in the gym more productive and better spent. If you have a preexisting condition or injury that means you can't run sprints, keep reading; there's equipment you can use to get around that.

First, let's look at what you're doing when you sprint.

At first glance the sprint looks like the quintessential speed exercise: it's all about running fast, after all.

But that' a misconception.

Sprinting isn't about speed, it's about speeding up

When you sprint, you're pushing back against the ground as hard and as fast as you can. Each stride needs to count; the direction of force is almost all forwards. Hamstrings and glutes are the major sources of sprinting power but the whole posterior chain and, to a lesser extent, the whole body, is involved. Once again, take a look at Olympic sprinters; they have some of the best physiques at the Games.

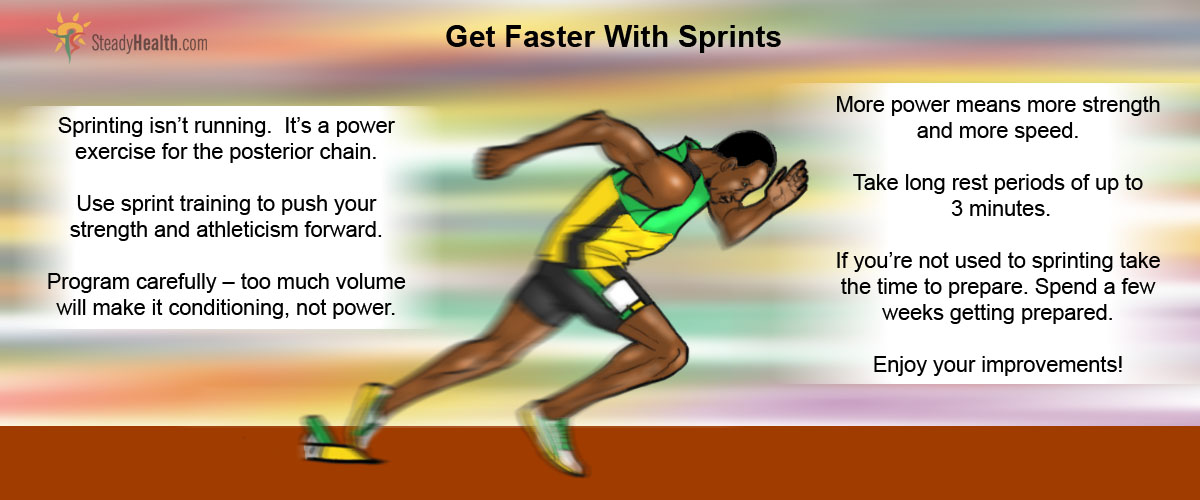

So when you sprint, it's not jogging but faster. It's a unilateral power exercise for the posterior chain.

What is 'power'? In sports terms power is 'increasingly fast strength' - explosive speed strength. Force is mass times acceleration - power is about increasing the acceleration, while raw strength work is about increasing the mass (weight) used. So it sounds like there's a relationship between the two?

Yes there is. At Westside Barbell, where the world's strongest powerlifters train, they have a power day, working on speed and force development in the three big powerlifting moves at loads of about 40-60% of the athletes' maxima. Why? Because mass is half the equation; acceleration is the other half.

Boosting your ability to accelerate equals boosting your ability to move mass. Bret Contreras, world renowned expert on posterior chain conditioning, says sprinters have the best voluntary glute activation of any athletes, including O-lifters and deadlift-loving powerlifters.

Does power improve speed?

Check out the documentary, 'Fastest Man Alive,' to see Usain Bolt sprinting with a 50lb sled and cranking out rep after rep of 135lb hang power cleans.

Runners achieve faster speeds by exerting more force against the ground in less time, while cyclists rely on forceful pedal strokes combined with rapid cadence. However, power isn't the sole determinant of speed. Technical proficiency plays a critical role; an athlete might possess considerable power but lack speed due to inefficient technique. Moreover, the demands of specific sports introduce nuances: sprinters prioritize power for short speed bursts, contrasting with marathoners who value endurance over sheer power.

Does it improve strength?

Ask Westside head honcho Louie Simmons, or his athletes like Laura Phelps - or like 3005-lb-totalling David Hoff, with his 1210lb squat and his reigning position as the strongest powerlifter - ever.

Conversely, building strength through resistance training can establish a foundation upon which power can be developed. To put it succinctly, while power training can contribute to increased strength, it's more accurate to say that a solid strength base is crucial for optimal power development.

Um, maybe it does...

While over at Westside they're training improved power in specific movements, power can be improved across the board. Power, like strength and speed, is partly a matter of muscle and partly of neurological activation. When you sprint, you improve the ability of the muscles in your posterior chain to contract and at the same time you train your central nervous system to produce power. That results in gains that can be applied across the board.

There's something else we haven't touched on yet, too.

See Also: The Cheapest Outdoor Activity: Advantages and Disadvantages of Running

For many people sprinting is a strength exercise

Huh?

When you sprint, the mass is the same - you're moving your bodyweight. But the acceleration is great. The greater the acceleration the greater the force, remember? When you sprint each leg produces force equal to many times your bodyweight. When Usain Bolt ran his record-breaker at the 2009 Berlin World Championships, a study in the European Journal of Physics found his average force output was over 800 Newtons; Mr. Bolt weighs 94 kilograms, equivalent to 94 Newtons. With each stride, Bolt pushed back against the track with a force equal to over four times his bodyweight. That means sprinting should have good carryover to strength, especially lower body strength, until you're relatively strong. It also means if you're "not"Â relatively strong and you jump straight into a sprinting program you could tear something. Paradoxically, going slower will get you there quicker; take time to prepare.

So I hope by now I've convinced you that sprinting is a good idea. Now I'd like to move on to how you should sprint, rather than why.

- Cressey, Eric, 'So You Want To Start Sprinting?' Ericcressey.com, March 28 2013, stored at http://www.ericcressey.com/so-you-want-to-start-sprinting, retrieved February 13, 2014

- J J Hernandez Gomez, V Marquina, R W Gomez, 'On the Performance of Usain Bolt in the 100m Sprint,' European Journal of Physics, 34: 1227, stored at http://iopscience.iop.org/0143-0807/34/5/1227/article, retrieved February 13, 2014

- 'Usain Bolt: Fastest Man Alive,' stored at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6cDmVNSYEk, retrieved February 13, 2014

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Michael Theis by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/huskyte/7648309262/

Your thoughts on this