The tightening in the chest, the sensation that a weight is suddenly placed on one’s heart, the unbearable pain, the indescribable pressure, all added to a feeling of impending doom; you would surely be familiar with all these symptoms if you have ever experienced a heart attack. And the more intense the pain is, the more severe the condition.

The pain of a heart attack tends to develop progressively; and just like physicians believe that the slower the pain progresses, the more delayed the treatment is; patients in turn tend to delay seeking treatment until the pain becomes excruciating and absolutely unbearable. But is this really the best way to go? And could early intervention give patients a better chance of survival?

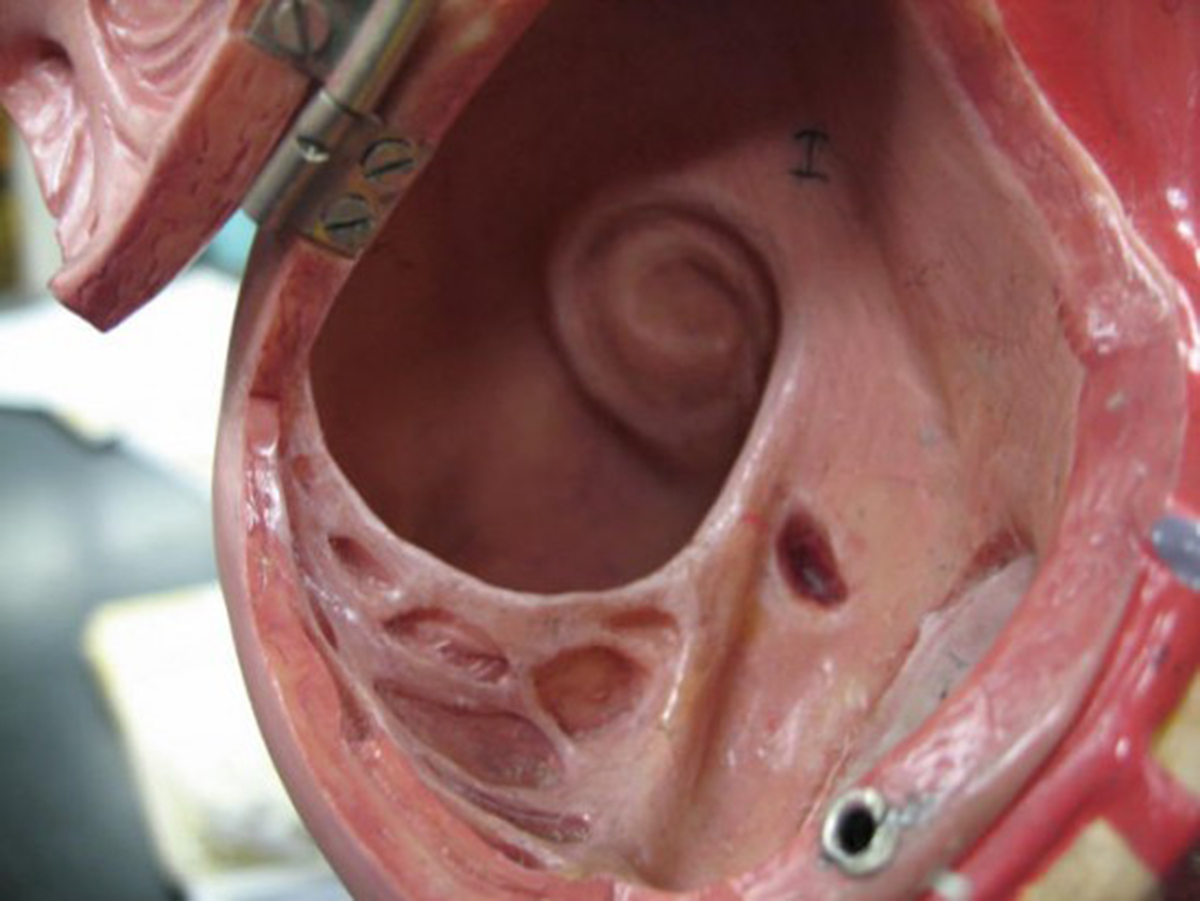

Understanding the Functioning of the Heart

A heart attack (medically known as myocardial infarction) is a medical condition in which the heart muscle is temporarily deprived of oxygen, causing it to stop pumping blood efficiently to the other organs.

Each and every organ of the body requires a certain “fuel” to function, including the heart. For all organs, that fuel is oxygen, distributed to via blood. However, due to the fact that the heart is the organ responsible for dispatching liters of blood to all the other organs, people tend to believe that the heart itself does not need blood to function, because it supposedly “have enough” (for instance, people might say that a beer factory that distributes beer to all retailers, stores and supermarkets does not need to purchase beer itself, as they are the main producers of their product). But it doesn’t work that way. As a matter of fact, that analogy is not possible when it comes to the functioning of the heart.

Blood is supplied to the heart via the coronary vessels which provide oxygen to the anterior, posterior, superior and inferior parts of the heart; including the four chambers (atria and ventricles). Collateral blood vessels also exist to reinforce the blood supply to this important organ, in order to ensure that enough blood is offered and to maintain the blood circulation in the event that one main artery gets blocked.

Read More: How Much Do You Know About Heart Attack?

The Importance Of Collateral Circulation

Now, suppose that one of the coronary arteries supplying blood to the heart get blocked. Should such an event occur, the part of the heart that is normally taken care of by the blocked artery would be in danger, as no more blood would be able to flow to that part. However, if there is collateral circulation (which means that other minor arteries also provide blood to the affected heart muscle), then there will be a continuous supply of oxygen. In people with coronary artery disease (occlusion of one of the coronary arteries with a cholesterol plaque or a thrombus), depending on how severe the obstruction is, collateral circulation could take time to develop and the heart would adjust to this new physiological state. This is why generally, in the early stages of myocardial infarction, there are no symptoms and the patient seems normal. However, as the obstruction continues to worsen, the collateral circulation is unable to compensate for the deficient blood supply, and this is when the patient starts experiencing the pain.

Heart Attack: The Mystery Behind The Excruciating Chest Pain

The actually etiology of the localized pain is due to the fact that under anaerobic conditions (lack of oxygen), the cardiac muscle releases lactic acid, an irritant that contributes to the chest pain. The anaerobic state automatically kicks in when the heart (or any other tissue) is deprived of oxygen long enough to cause an effect. Thus, lactic acid build-up causes constriction of the blood vessels, which results in chest pain. Another explanation for the chest pain is the forceful work of the cardiac muscle that tries to pump and push out blood to other organs despite its own lack of energy and strength. The heart has to keep pumping (or at least keep trying), and it would only stop when you die.

A Pain That Moves All Around

Sometimes, people who suffer from a heart attack identify the pain as one that is primarily localized in the chest, but then radiates to other areas such as the shoulder, the left arm or even the jaw. The reason for this is quite simple: the heart has only few nocireceptors (receptors for pain), and sometimes it is difficult for the brain to identify and specifically localize pain signals coming only from the heart. The sensory nerves from the heart join with other neurons and follow their pathway, which could explain while heart attack pain can be referred to other parts of the body. Additionally, when the sensory nerves from the heart are on their way to the brain, co-stimulation of other visceral neurons (neurons from other organs) can occur, leading to the concurrent finding of radiating pain.

Plain and simple - our body is like a vast communication network. The nerves act as the "wires" in this network, sending messages from various parts to the brain. When something's wrong in one part of the body, the nerves can send out signals that the brain might interpret as pain.

Now, imagine the heart as a house in a large neighborhood (the body). If there's a fire (damage) in that house, the smoke alarms (pain signals) might go off not just in that house but also in neighboring houses. This is because the heart's "alarm system" is closely connected to other areas like the arm, jaw, and back.

In the case of the heart, if it's not getting enough blood (because of blocked arteries or other reasons), it sends out an alarm in the form of pain. But the heart's nerve signals are a bit messy. Instead of just signaling pain in the heart, the brain sometimes gets confused and thinks other areas are in trouble too. This is why someone having a heart attack might feel pain in the chest, but also in the left arm, jaw, or back. The pain "radiates" because the brain is misinterpreting where the trouble (or "fire") is actually located.

In essence, radiating pain during a heart attack is like a faulty alarm system. The heart's trying to signal distress, but the brain gets mixed messages about where the problem really is. And that's why it's crucial to recognize and act on these signals, even if they seem to be coming from different places.

Read More: Are You At Risk Of Having A Heart Attack?

Delay in Seeking Treatment

Generally, we don’t go to the hospital (or we don’t consult a doctor) unless something is significant enough to disrupt our daily routine and to prevent us from completing our activities. And quite frankly, we wouldn’t blame anyone for it, because we don’t fix things that are not broken, do we?

Unfortunately though, this ugly truth also applies to life-threatening conditions like heart attacks. Because the initial chest pain is not severe enough, patients (except for those who are overly concerned with their health) would not seek medical help, and would rather attribute their pain to some random medical conditions. Unfortunately, a heart attack always presents at its terminal stages, when only little can be done (symptoms management is the way to go for Doctors). From that point on we cannot go back, and all that is left to do is simply ensure that the condition doesn’t worsen overtime. Henceforth, after a heart attack physicians recommend lifestyle readjustments: strict diet, minimal exercise, low stress levels, etc.

However, what we could do is to sensitize patients to seek medical treatments as soon as they experience episodes of pain and chest discomfort. This might not save all the lives lost to a heart attack, but at least it could implement preventive measures and eventually decrease the mortality rate of myocardial infarction.

- Photo courtesy of shutterstock.com

- Photo courtesy of GreenFlames09 by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/greenflames09/74297146

Your thoughts on this