Table of Contents

For about 40 years after their introduction in the 1940's, antibiotics were the world's wonder drug.

The most effective method humans had ever devised to kill the bacteria that cause dangerous, sometimes deadly, infections, antibiotics became widely available and cheap. About 1980, however, a serious problem arose in using antibiotics. The "bugs" seemed to have "figured out" a way to defeat them.

The problem that appeared several decades ago and that is becoming critical now is antibiotic resistance. Not every individual bacterium reacts to an antibiotic in exactly the same way.

It's important to use all of a prescribed course of antibiotics to kill even the strongest bacteria so they don't come back--without any neighbors to keep them in check. And it's important not to use antibiotics for conditions that don't respond to antibiotics, like viral infections. However, enough doctors have prescribe enough antibiotics irresponsibly, and enough people have used enough antibiotics irresponsibly, that antibiotics are not as reliable and don't treat as many different infections as they used to.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is especially acute for infections with the bacterium Clostridium difficile. Clostridium is an infection of the bowel. It can spread when food or beverages are contaminated with the feces of a person who has a Clostridium infection, or it can be spread by inhalation of spores, especially in hospitals and emergency rooms.

Clostridium infections often only cause mild symptoms such as:

- Abdominal cramps.

- Mild but unremitting diarrhea, and

- Fever.

However, Clostridium infections can also aggravate a condition known as ulcerative colitis. When this happens, the lining of the bowel becomes inflamed, and may even begin to break down. The contents of the bowel can leak into the bloodstream, and a particularly pernicious form of gangrene can lead to an agonizing death.

In the United States, Clostridium is usually a disease you catch when you are hospitalized. Hospital rooms may be contaminated with spores of the bacterium. And hospital patients are often on antibiotics that kill other kinds of bacteria that keep Clostridium in check.

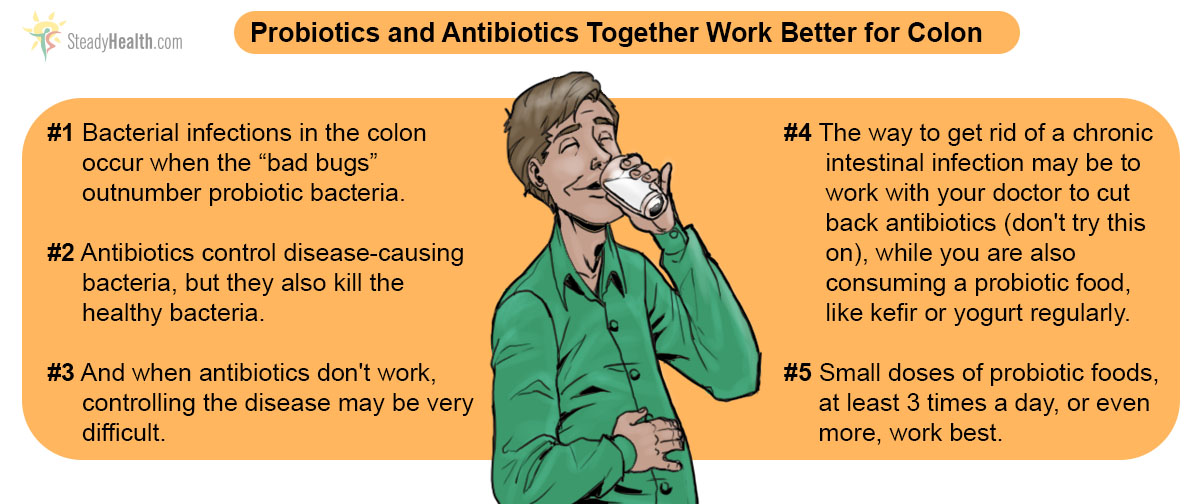

These bacteria can release toxins that break down the lining of the colon, but they are usually kept in check by all the other trillions of bacteria that also live in the gut.

See Also: Prebiotics and Probiotics: What's the buzz?

When antibiotics kill competing bacteria, however, Clostridium is free to multiply. As it multiplies unchecked, it begins to break down the gut. How much damage the infection can do depends on how many other bacteria survive, or on antibiotic treatment that kills the Clostridium itself.

But that's the problem. The vancomycin antibiotic and the metronidazole antifungal that used to be able to keep Clostridium in check just don't work 5 to 30% of the time. Lives of patients are put in danger. Dr. Johan S. Bakken, from St. Luke's Hospital and the University of Minnesota Medical School Duluth in Minnesota in the USA, however, offers a solution.

- Bakken JS. Staggered and Tapered Antibiotic Withdrawal With Administration of Kefir for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Jun 9. pii: ciu429. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 24917658.

- Mindmap by steadyhealth.com

- Photo courtesy of Helena Price by Flickr : www.flickr.com/photos/helenadagmar/3436335443

Your thoughts on this